Having been here, there, and everywhere in recent weeks (I’ll put out more posts shortly on the ‘there’ and the ‘everywhere’), I’m dreadfully behind at present with announcements of EMLO’s latest catalogues, for which apologies to all concerned. In the first instance, I’m acutely aware that publication of the inventory of the Huguenot refugee Jean Claude’s correspondence a full two-and-a-half weeks ago is still to be celebrated.

Despite experiencing intensifying persecution, Jean Claude (1619–1687) persisted in his attempts to explain and defend the Calvinist religion through the delivery of sermons, participation in disputations, and via the publication and circulation of learned treatises. Ever a defendant of Calvinist theology, Claude was reluctant to leave his native France, even to the extent of declining the offer of the chair in theology at the University of Groningen and preferring to remain at his church. The Frenchman fled finally to Dutch Republic only when, following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes on 22 October 1685, he was given just twenty-four hours to leave the country. Having worked ceaselessly for the Calvinist cause in Nîmes, Montauban, and — from 1666 — at the Huguenot temple at Charenton, the pastor headed north with his wife, Elisabeth, for a reunion in The Hague with their son Isaac, who had moved and settled in the city three years previously.

The inventory of Claude’s letters forms part of a converging cluster of Huguenot correspondence in EMLO that will increase significantly later this year. The correspondence has been calendared by Dr David van der Linden, a scholar based at the University of Groningen. Dr van der Linden has published extensively on Huguenots in the Dutch Republic (see Experiencing Exile: Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Republic, 1680–1700)[1. David van der Linden, Experiencing Exile: Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Republic, 1680–1700 (Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 2015).] and he is involved in a number of related research projects, including Divided by Memory: Coping with Religious Diversity in Post-Civil War France, 1598–1685 and the pioneering initiative Signed, Sealed, and Undelivered. The research team focussed on the latter is hard at work investigating, cataloguing, and describing the material features of the extraordinary and fascinating postal archive known as the Brienne Collection, which is now in the care of the Museum voor Communicatie in The Hague.

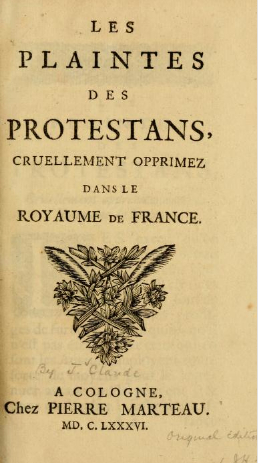

Title-page of Jean Claude’s 1686 publication. (Source of image: Internet Archive)

Claude survived only for a year after his flight, despite the receipt of a pension from William of Orange and the States of Holland and his appointment to the position of historiographer. In these final months of his life, however, he was able to write and publish an account of the persecuted Huguenots, Les Plaintes des protestans cruellement opprimez dans le royaume de France (1686).[2. Les Plaintes des protestans cruellement opprimez dans le royaume de France (Cologne: Pierre Marteau, 1686); available on open access on The Internet Archive.] Translated from French into English, both language versions were subjected soon after publication to an ordeal in London where, according to the diarist John Evelyn, at the order of James II:

‘This day [5 May 1686] was burnt, in the old Exchange, by the publique Hang-man, a booke (supposed to be written by the famous Monsieur Claude) relating the horrid massacres & barbarous proceedings of the Fr: King against his Protestant subjects, without any refutation, that might convince it of any thing false: so mighty a power & ascendent here, had the French Ambassador: doubtlesse in greate Indignation at the pious & truly generous Charity of all the Nation, for the reliefe of those miserable sufferers, who came over for shelter: About this time also, The Duke of Savoy, instigated by the Fr: King to exterpate the Protestants of Piemont, slew many thousands of those innocent people, so as there seemed to be a universal designe to destroy all that would not Masse it, thro out Europ, as they had power, quod avertat D.O.M.'[3. John Evelyn, The diary of John Evelyn, volume 4: 1673–1689, ed. E. S. de Beer (Oxford: OUP, 1955), pp. 501–11; available on Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO), but requires access from a subscribing institution.]

I’ve included a link to Claude’s final work; it’s well worth the read.