Celebrations are afoot in The Hague following the reopening last weekend of the city’s Museum voor Communicatie [COMM]. This museum, which has been undergoing renovation for the past eighteen months, was established in 1929 around the collections of the philatelist Pieter Wilhelm Waller (1869–1938) and is dedicated to the history of post and telecommunications.[1. Waller was the author of De eerste postzegels van Nederland: uitgifte 1852 (Haarlem: Enschedé, 1934).] As COMM throws open its doors on a range of new vibrant and engaging exhibits, at EMLO we would like to draw attention to the catalogue of the remarkable corpus of letters known as the Brienne Collection which resides in its care.

Celebrations are afoot in The Hague following the reopening last weekend of the city’s Museum voor Communicatie [COMM]. This museum, which has been undergoing renovation for the past eighteen months, was established in 1929 around the collections of the philatelist Pieter Wilhelm Waller (1869–1938) and is dedicated to the history of post and telecommunications.[1. Waller was the author of De eerste postzegels van Nederland: uitgifte 1852 (Haarlem: Enschedé, 1934).] As COMM throws open its doors on a range of new vibrant and engaging exhibits, at EMLO we would like to draw attention to the catalogue of the remarkable corpus of letters known as the Brienne Collection which resides in its care.

This veritable treasure trove is made up of approximately 2,600 letters, although the precise number is still to be determined. Over the course of the seventeen years between 1689 and 1706, not one of these letters, for a myriad of evocative and mundane reasons, reached the hands of its intended recipient. Rather, each undelivered (or ‘dead’) letter was retained in The Hague as property of the Postmaster and (until her death in 1703) Postmistress. Simon and Marie Brienne were responsible for mail both to and from ‘the city of Antwerp and all surrounding places and cities in Brabant, France, Flanders, Mons in Hainaut, and Spain’.[2. Simon took office in 1676 and retained the position until his death in 1707. See the Charter appointing Simon de Brienne as postmaster, The Hague, 13 January 1676, Gemeentearchief, Delft, Weeskamer nr. 11851, and Rebekah Ahrendt and David van der Linden, ‘The Postmasters’ Piggy Bank. Experiencing the Accidental Archive’, in French Historical Studies, 40, 2 (2017), p. 200, and note 21.] The undelivered letters (which have been the subject of a couple of previous posts on this blog) are being examined and catalogued at present in meticulous and methodical detail by our partners the Signed, Sealed, and Undelivered project.[3. See Hadriaan Beverland, routes to and from the Dutch Republic, and the postmasters Brienne and Reading the folds: students of letter-locking.] To coincide with the reopening of COMM, we are delighted to release into EMLO metadata for the first batch of letters from the Collection and to inform you that further ‘installments’ will be uploaded over the coming months.

New metadata fields in EMLO include letterlocking details and date of receipt.

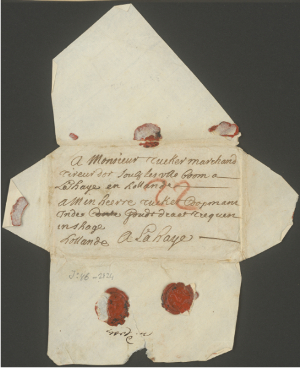

We hope EMLO’s users will seize the opportunity to explore these pioneering records both with respect to content (each letter has been photographed and images made available for consultation) as well as for the richness of details collated. Over the past year, EMLO has worked particularly closely with the SSU team. A week-long workshop dedicated to scrutiny of the metadata that could and should be captured for these remarkable letters was held in Oxford last March and provided the ideal opportunity for the two projects to discuss a number of fields which had not been considered in the epistolary data model when construction of EMLO-Edit took place back in 2010. As Cultures of Knowledge set out to create its pilot union catalogue of scholarly correspondence, the assumption was that (almost always) the manuscript letters under consideration — whether draft, letter sent, copy, or extract — would be conserved flat, as is usual in all the libraries with which we work. Not in our wildest (epistolary) dreams did we anticipate the inclusion of thousands of letters that had been sealed and sent, but not received and opened. Yet the Brienne Collection — with approximately six hundred letters that have managed to evade earlier curatorial ‘intervention’ and as a result have remained locked and sealed for more than three centuries (and will continue thus in perpetuity, thanks to the considered ethos of the SSU project and to enlightened curation at the museum, their contents revealed to us instead by use of ‘non-invasive’ scanning procedures) and more than two thousand with broken seals that are stored still today as folded originally — has opened up a compelling new field of study.

A wrapper (DB-2124) from the Brienne Collection. (Museum voor Communicatie [COMM])

The discussions held between the two projects resulted in the rolling up of sleeves (in particular by Oxford’s developer Mat Wilcoxson) and we are exceptionally pleased to report that EMLO is able now to capture and store a range of new fields, including those for the folding, wrapping, and letterlocking metadata; the postal route a letter is recorded to have taken; date(s) of receipt (which have been set out in other EMLO catalogues hitherto as a ‘general note’ rather than in a dedicated field — as you will find with, for example, the calendars of correspondence compiled by Alexandre J. Tessier for both John Doddington and Francis Vernon); and the reason for non-delivery (many of which are heart-breaking when considered alongside the content of the letter). With fitting serendipity, the Brienne Collection — described so beautifully as an ‘accidental archive’ by Rebekah Ahrendt and David van der Linden — has provided the ideal opportunity to expand EMLO’s data model, whilst what is written in the letters contained therein present for historians a plethora of insights into early modern lives and events that otherwise would have been lost entirely.[4. See Rebekah Ahrendt and David van der Linden, ‘The Postmasters’ Piggy Bank. Experiencing the Accidental Archive’, in French Historical Studies, 40, 2 (2017), pp. 189–213.] In Ahrendt and van der Linden’s words, these letters represent ‘the thoughts, cares, and dreams of a cross section of society: ambassadors, dukes and duchesses, merchants, publishers, spies, actors, musicians, lovers, parents, expatriates, refugees, women as well as men. Here is an archive that will let the voices of the past speak again.'[5. Ibid., p. 190.]