‘Of the innumerable men whom I have heard lecture from the rostrum, I call three men the greatest: Petavius, Vossius and Varlaeus. However, Vossius stood above them as the cypress trees stand above the tedious undergrowth.'[1. See C. S. M. Rademaker, Life and Work of Gerardus Joannes Vossius (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1981), p. 245.] Thus wrote the French physician Samuel Sorbière of the polymath Gerardus Joannes Vossius (and presumably with a nod to Virgil when speaking of Rome).[2. Virgil, Eclogue I, lines 24–6.] Vossius, whose catalogue is launched in EMLO this week, is a towering figure in any number of significant ways, not least with respect to his correspondence.

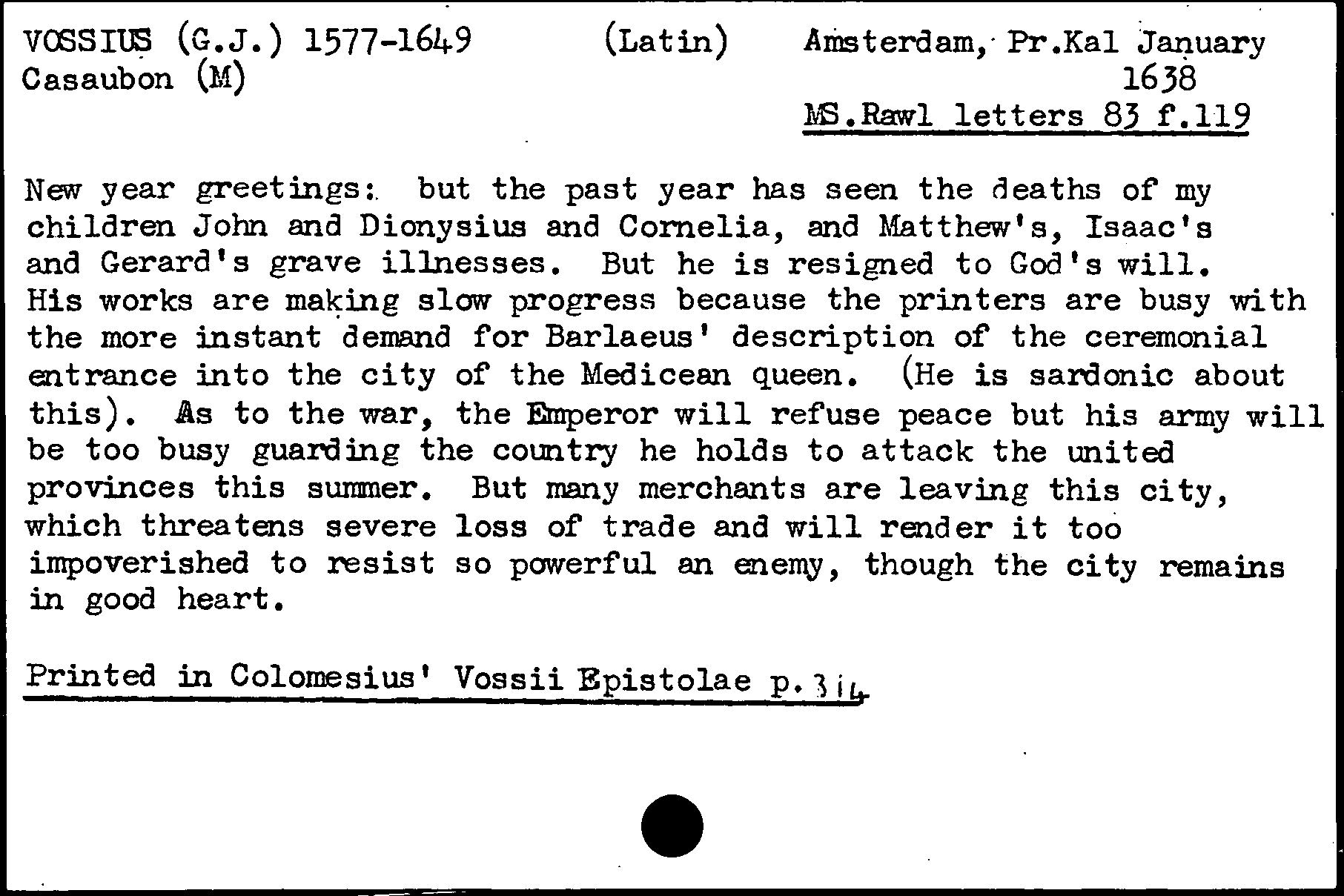

Since the earliest days of Cultures of Knowledge, Vossius has been central to the project’s work. EMLO’s database was constructed around the Bodleian card catalogue records, which include the letter collections amassed in the first half of the eighteenth-century by the antiquarian Richard Rawlinson. Vossius’s letters to be found in Rawlinson’s collection comprise the Dutch scholar’s own letter books and contain, therefore, the holograph letters he received, together with copies of his outgoing correspondence. These copies were made either by Vossius himself, or by his sons, or by the students who lodged at the Vos family home, a house in which it was not just the males who were given care and attention. Vossius’s much-loved daughter, Cornelia, who drowned tragically in 1638 following an accident on the ice that involved the sledge in which she was travelling from Amsterdam to Leiden, is known to have been extremely well educated and versed in an impressive number of languages.  Vossius comes across loud and clear in his correspondence not only as a significant scholar but also as an exceptionally kind and caring individual and family man. When starting working with Bodleian card catalogue records six years ago, it struck me how often and how deeply this man mourned the deaths of those he loved — members of his family and his children, his friends — as well as how he sympathized with and sent comfort to a wide range of correspondents as they struggled to endure similar sorrow and bereavement.

Vossius comes across loud and clear in his correspondence not only as a significant scholar but also as an exceptionally kind and caring individual and family man. When starting working with Bodleian card catalogue records six years ago, it struck me how often and how deeply this man mourned the deaths of those he loved — members of his family and his children, his friends — as well as how he sympathized with and sent comfort to a wide range of correspondents as they struggled to endure similar sorrow and bereavement.

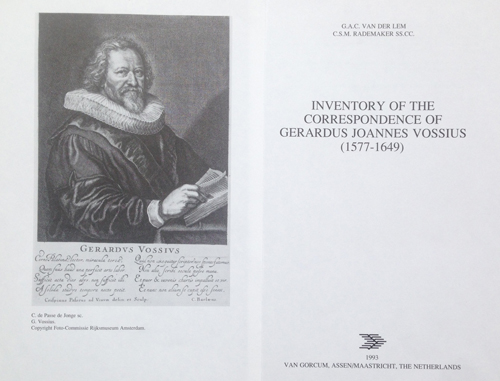

In the spirit of making catalogues available at the earliest opportunity, Cultures of Knowledge published the Bodleian card catalogue records back in 2012 on the occasion of the launch of EMLO, and today we are uploading metadata taken from the inventory compiled by the renowned Vossius scholars C. S. M. Rademaker and G. A. C. van der Lem.[3. G. A. C. van der Lem and C. S. M. Rademaker, Inventory of the Correspondence of Gerardus Joannes Vossius (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1993).]

G. A. C. van der Lem and C. S. M. Rademaker, ‘Inventory of the Correspondence of Gerardus Joannes Vossius (1577–1649)’ (Assen and Maastricht: Van Gorcum, 1993).

Work is ongoing in EMLO to link the dual interpretations for each letter. Thanks to the generous gift of the meticulously ordered working notes and facsimiles (pictured below in their boxes on the shelves in my office) used by Anton van der Lem and Cor Rademaker as they worked on Vossius’s vast correspondence, we are able to tidy up simultaneously many of the mistakes contained within the Bodleian card catalogue’s person records. The inventory these two scholars brought out in print in 1993 serves as an invaluable finding-aid for the complete correspondence, and should anyone be interested in pursuing work with the texts of Vossius’s letters, please be in touch with us at EMLO as the underlying metadata could provide a firm base upon which future work might be layered. Equally, should scholars be interested in working with the networks of which G. J. Vossius formed a part (together with those of his son Isaac, whose calendar of correspondence was published last year in EMLO by the Leiden-based scholar Dr Robin Buning), we would be delighted to help in every way possible.

Vossius died in 1649, at the age of seventy-one (or seventy-two, depending on the exact day of his birth), of erysipela, a streptococcal infection of the skin, also known as St Anthony’s Fire. The stories of the events preceding his death vary. One holds that he had a disagreement with a bookseller, became tremendously upset, returned home, laid down and died; another recounted how he was at work in his library, the ladder up which he climbed broke, and he was crushed under falling folio volumes.[4. Rademaker, op. cit., above, p. 343.] Either or neither may be true but, however he met his end, Vossius’s letters are lasting proof that the world lost with his passing a kind, generous, considerate man who was — in the words of the scholars who focussed upon him — one of the ‘finest representatives of late humanism’.[5. Van der Lem and Rademaker, op. cit., above, p. VII.]