‘I Elias Ashmole, was the son (& only Child) of Simon Ashmole of Lichfeild Sadler eldest son to Mr. Thomas Ashmole of the said Citty Sadler, twice cheife Bayliff of that Corporation, and of Anne one of the daughters of Anthony Bowyer of the Citty of Coventry draper, & Bridget his wife only daughter to Mr: Fitch of Ansley in the County of Warwick gent. I was borne the 23rd of May 1617 (& as my deare & good Mother hath often told me) neere halfe an houre after 3 a’clock in the Morning.’ Thus, at the beginning of a set of autobiographical notes, Elias Ashmole wrote of his birth four hundred years ago today. In celebration of this event, EMLO is delighted to announce the publication of a new catalogue containing a calendar of his correspondence.

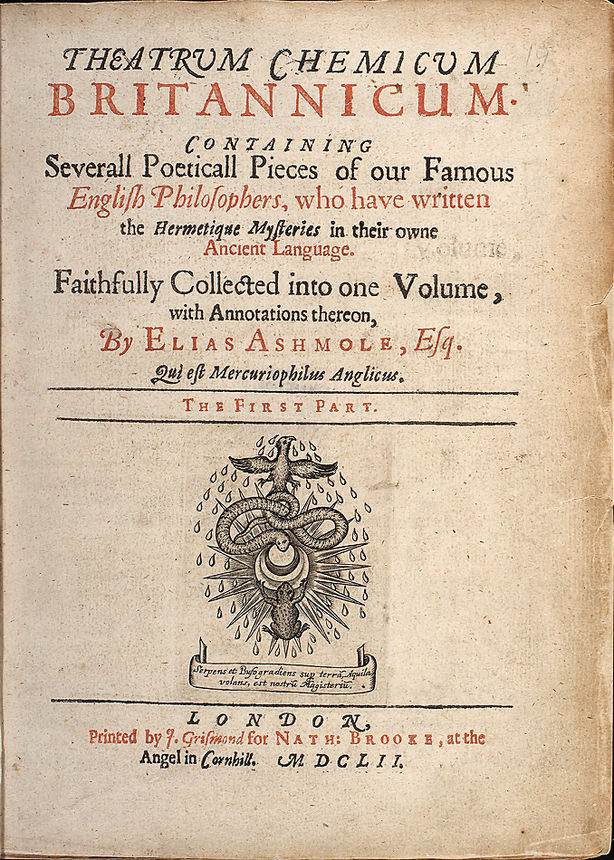

Cover (page A1r) of ‘Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum’, by Elias Ashmole. 1652. (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons, from http://dewey.library.upenn.edu/)

Ashmole is a complex character known best as a collector, an antiquary, and the founder of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. But he was also a freemason, an inaugural Fellow of the Royal Society, an astrologer (with a particular interest in alchemy, publishing Fasciculus chemicus in 1650, Theatrum chemicum Britannicum two years later, and The Way to Bliss in 1658), as well as an officer-of-arms and herald, and the Comptroller, and later Accountant-General, of the Excise. He began his working life as a lawyer. Many of the events that befell him we know only from his own account in a document preserved among his papers in the Bodleian Libraries (MS. Ashm. 1136, fols 2–98). For one-hundred-and-thirty years after his death, this manuscript was considered to be a diary. It took the eighteenth-century antiquary and diarist Thomas Hearne (whose own correspondence plays such a crucial role in the early years of the Bodleian’s analogue Index of Literary Correspondence) to observe: ‘It is most wretched Stuff, and put down by Mr Ashmole only as private Memorandums’.[1. See C. H. Josten, ed., Elias Ashmole: His Autobiographical and Historical Notes, his Correspondence, and Other Contemporary Sources Relating to his Life and Work, 5 vols (Oxford: OUP, 1967), vol. 1, p. 4.] And Hearne was right: it is a predominently chronological listing of autobiographical notes compiled in the years from 1678 when Ashmole was sixty-one. The register continues until 1687, five years before his death, and must have been intended as the outline of an ultimately unwritten autobiography. It is from these jottings that Helen Watt — who worked from 2009–12 on the correspondence of the Ashmolean’s second keeper, Edward Lhwyd — has teased out this calendar of correspondence. Far from straightforward work, it is the first time that the metadata for Ashmole’s letters have been set out in this way.

Portrait of Elias Ashmole, by John Riley; frame made by Grinling Gibbons. 1681–2. (Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford; WA1898.36)

Working in partnership with Oxford University Press — the publisher of C. H. Josten’s 1966 ‘monumental edition of materials relating to Elias Ashmole’ (as described by Charles Webster)[2. See Charles Webster’s review in The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 4, no. 1 (June 1968), pp. 72–3.] — and with its digital resource Oxford Scholarly Editions Online [OSEO], Helen has linked the records of letters in EMLO to the online edition and has supplemented the body of letters to be found in Ashmole’s listings with detailed calendaring of a set of prognostications on the weather (Bodleian Libraries, MS. Ashm. 368). These forecasts were sent monthly to Ashmole for twelve years from 1677 by John Goad, the headmaster of the Merchant Taylors’ School in London. What has been drawn together in EMLO is in the main a subjective calendar; we have been able to record only what Ashmole wished to remember. Correspondence that relates to his dealings with the Tradescants is missing, for example, as is that concerned with a number of law suits in which he was involved, but this calendar is a start and as additional letters are brought to our attention, we will augment the catalogue. For EMLO’s users who are interested in alchemy, in heraldry, in the history of collecting, or in early medical practices (Ashmole was a meticulous note-taker when it came to his own health), it’s well worth sinking into a chair in a OSEO-subscribing library and following the links from each letter record to Josten’s edition online. For it is here you will find a myriad of choice snippets. Consider, for example, the following remedy Ashmole availed himself of on 11 April 1681: ‘I tooke early in the Morning [a] good dose of Elixer, … hung 3 Spiders about my Neck … they drove my Ague away, Deo gratias.'[3. Josten, vol. 4, p. 1680.] If only more conditions were cured this easily!

I’m extremely glad, Mr Ashmole, that you survived such self-medication to live another eleven years. Happy four-hundredth birthday!