In these troubled times of trenches, walls, and drawbridges, we could not be more delighted to announce the arrival in EMLO of Pierre Bayle, one of the foremost citizens of early modern Europe’s Republic of Letters. Bayle resides at the very heart of this early modern community that corresponded and networked irrespective of political border or scholarly allegiance, and today we — together with our own international network of twenty-first century historians — remain firmly committed to its reassembly.

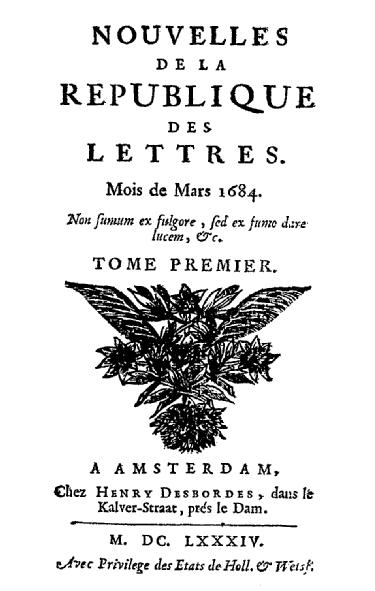

‘Nouvelles de la République des Lettres’, no. 1 (Amsterdam: 1684; source of image: Wikimedia Commons).

A Huguenot refugee who moved to Rotterdam shortly before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, Bayle published one of the first literary periodicals, the Nouvelles de la république des lettres (1684–1687); he compiled the vast and remarkable Dictionnaire Historique et Critique in two editions of 1697 and 1702; and in his Commentaire philosophique (1686–1688) he issued a plea for religious tolerance based on moral rationalism. A critical edition of his extensive correspondence is being published in print and online. The Voltaire Foundation, our esteemed partner here at the University of Oxford, is publisher of the multi-volumed hard-copy edition (under the direction of Antony McKenna and the late Elisabeth Labrousse), and publication of the impressive thirteenth volume (containing the correspondence from the years 1703 to 1706) has just been celebrated. The digital edition of the correspondence — overseen also by Professor McKenna — is hosted at the Université Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne, and it is on this interface that the letters may be consulted together with images of the manuscripts. In EMLO you will find at present a calendar of the metadata of the first seven volumes of Bayle’s letters, each record of which provides a detailed reference to the hard-copy edition and offers a link to the digital copy mounted at Saint-Étienne. Two incremental extensions to the calendar will be added over the coming months until the total of 1,791 letters is in place.

But of course, these letters are the ones that that have survived. As Professor McKenna explains in his thorough and informative introduction to the catalogue, Bayle’s ‘surviving letters bear witness to a great number of letters that have not’. For example, the two hundred extant letters dated prior to October 1681 refer to more than 400 others that have been lost. Consideration of these missing letters leads to Bayle’s network becoming ‘much more complex and significantly more dense’, Professor McKenna oberves. We will be working together in the coming months to explore this shadow archive and the extent of the networks that held Bayle at their heart. Keep watching: this drawbridge is firmly down and there is a great deal more to come!