(source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

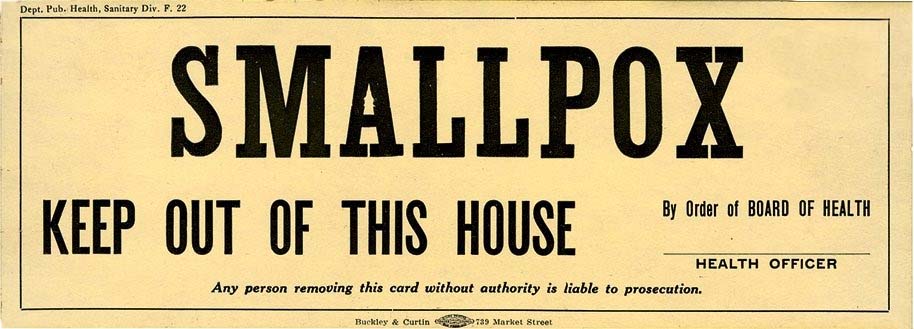

Smallpox — which became known as ‘small’ only in the mid-sixteenth century to distinguish it from ‘great’ or ‘French’ pox [syphilis] — was a scourge of the early modern era. The physician whose catalogue is published in EMLO this week, James Jurin, worked in his capacity as Secretary of The Royal Society to collate statistics both for mortality amongst smallpox patients and for the immunity and survival of volunteers following variolation, a practice that involved inserting powdered smallpox scabs or fluid from the pustules into scratches made in the skin of a healthy individual. Jurin, who held the position of Secretary between 1722 and 1727, advertised in the Philosophical Transactions for physicians’ accounts of their trials and experiences with variolation and the subsequent survival or infection rates; from the responses received, he calculated the odds of mortality following inoculation. By the early eighteenth century, smallpox was rampant in every known continent. It carried a mean mortality rate that lay somewhere between 25 and 30% and survivors were left with extensive and disfiguring scars and sometimes also blindness. Over sixty individuals across Britain responded to Jurin’s call for information and, based on the accounts in their letters, he compiled mortality figures for instances of inoculated, as well as for naturally contracted, smallpox. He published these figures annually. Although a physician with practices in London and in Tunbridge Wells, Jurin did not administer variolation himself, and he arranged for his own daughters to undergo the procedure with Robert Baker, a surgeon at Guy’s Hospital. Jurin’s statistics were important, however, and ultimately played a part in the struggle to eradicate this disease, contributing to the body of knowledge upon which Edward Jenner was able to build later in the century. The last case of naturally occurring smallpox was diagnosed in 1977.

Although Jurin is known best for his epidemiological work, he was also an active correspondent who maintained contacts the length and breadth of Europe and engaged with a number of the public controversies that played out in the early eighteenth-century. In 1741, Voltaire wrote to him proclaiming: ‘who loves truth ought to read . . . especially mr jurin.’ The calendar of correspondence available in EMLO today has been taken from the letters collected in Andrea Rusnock’s impressive publication (brought out in 1996 by Editions Rodopi and in which transcriptions of many of the letters may be consulted), and work to collate this metadata in EMLO was undertaken at the suggestion of Richard Aspin at the Wellcome Library, London.

As we celebrate the correspondence of one secretary of the Royal Society, we are pleased to announce also that metadata for an additional 753 letters in the correspondence of his illustrious predecessor Henry Oldenburg have been released, bringing the current total in that catalogue to 1,956 records. In addition, metadata taken from the correspondences of many more early fellows of the Royal Society are in preparation at present and will be entered into EMLO in the course of the coming months.