Christmas is just around the corner and for those with young children this may well entail – as well as wrapping late and waking early – obligatory attendance at the traditional school plays that re-enact a particularly famous birth. The Nativity may be unique, but whether for celebration, ritual or act of witness, the account of a birth has a real potency, and rarely more so than in the context of dynastic royalty.

At the tail end of a heady year, during which we saw the lenses of the world’s press focussed on a small royal bundle in west London, we — through the prism of EMLO — have been able to glimpse through letters the circumstances and conditions surrounding a spectrum of early modern births, and we’d like to offer you a seasonal roundup of epistolary nurslings, centred on a particularly interesting account of a royal arrival from 1688.

In the catalogue, we often witness the arrival of royalty. On the very day Henry VIII’s long-awaited heir to the throne, the future Edward VI, was born, his mother — poor, doomed Jane Seymour — wrote to convey her ‘good tidings’ to the Privy Council (on the verso of this copy made by Thomas Hearne, a report is set out charting her worsening and ultimately fatal condition). We read of the birth of Charles I, son of James VI and I and Anne of Denmark and, in turn, find letters concerning the later pregnancies of Charles’s wife, Henrietta Maria: both Henry, Duke of Gloucester, and Henriette, later Duchess d’Orléans, were conceived and delivered during the height of the Civil War, and their mother appears to have set great store by a favoured midwife. In 1644 when pregnant with Henriette, the Queen left her husband in Oxford for the relative safety of Exeter. On this occasion, Captain Thomas Allin was charged by Henry Jermyn to take ‘especial care’ of her midwife, while the King, who was otherwise engaged in the run up to Marston Moor, pleaded with trusted physician Theodore Mayerne to journey from London to oversee the birth (a summons which, ‘age and corpulency notwithstanding’, was obeyed).

1688: ‘The Joyful News of a Young Prince’

It is no surprise that, in the decades following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, we find a plethora of correspondence concerning the circumstances of the birth of James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1786), the ‘Old Pretender’. For those who might like a brief refresher on events surrounding this particular regal delivery, Mary of Modena, the Catholic wife of James II, had suffered numerous miscarriages and the children who had been born alive had, until this point, been short-lived. The implications of a Catholic heir were all too apparent in late-seventeenth century England, and as each royal pregnancy progressed rumours had circulated the length and breadth of the country that the birth would be faked and a healthy child substituted. In June 1688, plans for the royal birth were changed at the eleventh hour — the Queen decided to remain at St James’s rather than travel to Windsor as arranged — and when James Edward was born to her on the morning of 10 June after a short labour (too quick, it was held, for certain officials to witness) the story spread like wildfire that the child was stillborn and that a fraudulent baby had been smuggled into the birthing room in a warming pan.

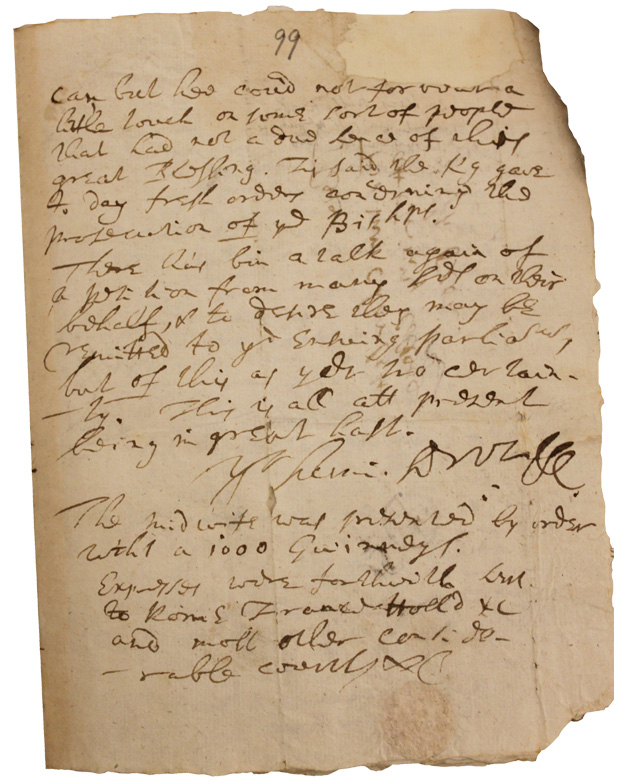

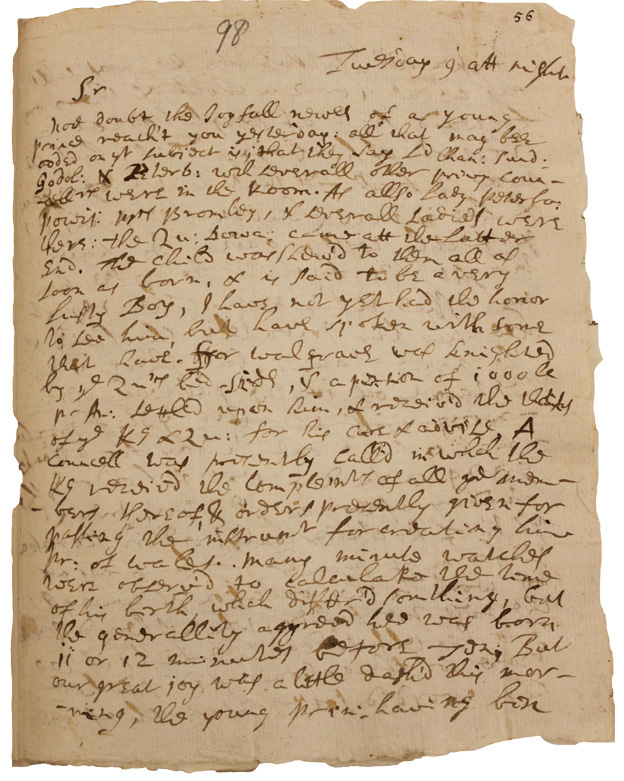

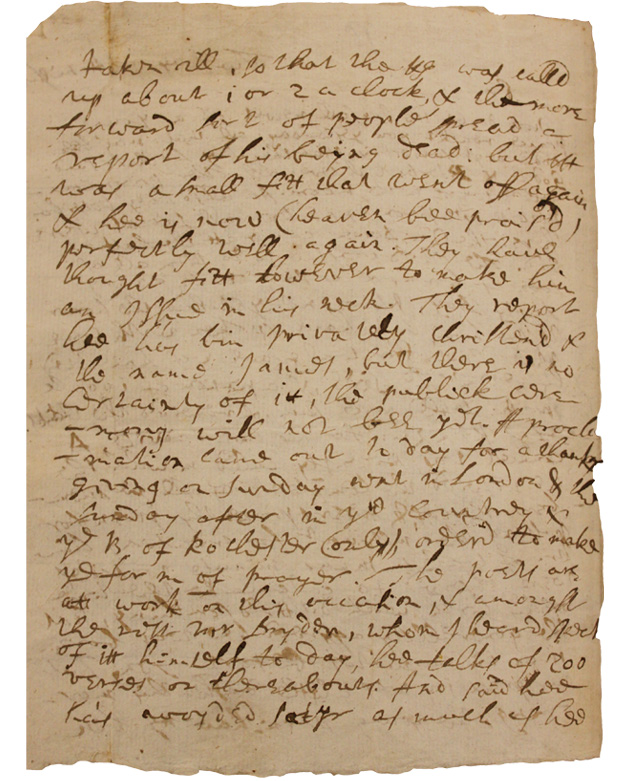

An interesting autograph letter, dated 9 June 1688 and reproduced below, provides fascinating insight into the case; sent two days after the event from a judge named Villiers Bathurst to the Oxford academic Arthur Charlett, it provides a blow-by-blow (although manifestly second-hand) account of a wholly legitimate arrival, and was clearly one of many ‘eyewitness’ testimonies, both manuscript and print, that circulated with royal encouragement after the birth. In a dashed and untidy scrawl, Bathurst reports ‘the joyful news of a young prince’, who was characterised as a ‘very lusty boy’ who was ‘show’d to them all [various assembled dignitaries] as soon as born’. While original estimates of the time of birth admittedly ‘differ’d’, it was ‘generally agreed hee was born 11 or 12 minutes before Ten’. Bathurst reports a brief panic (‘[O]ur great joy was a little dash’d this morning, the young prince, having been taken ill… and the more forward of people… spread a report of his being dead’), but it turned out to be ‘a small fitt that went off again’, and in characteristic fashion he’s soon feverishly speculating on names: ‘They report he has been privately christened the name James, but there is no certainty of it’. In an intriguing postscript, he reports the staggeringly large sum of ‘1000 Guinneys’ being paid to the midwife by way of remuneration.

MS Ballard 22, fol. 98. Image reproduced by courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford [2013].

Everyday Birthing

The political and cultural significance of succession and royal births notwithstanding, it’s poignant to read of the pregnancies and birthing experiences of ordinary women. Labour is a difficult process; mortality rates are high. Small gifts are presented to certain women in confinement and, ever a costly business, midwives and nurses require payment. Following news of her cousin’s safe delivery in 1672, and in contrast to the princely sum mentioned above, Lady Elizabeth Astley sends ‘3 pennies which I desire may be disposed of to the midwife and nurses’. Eighteen years later, one Antony Cope begs Archbishop William Sancroft for financial aid for the same purpose: ‘He has been lodged in Peter Street Westminster for 11 months with his wife and five children, now increased to six, involving the charge for a midwife’. Before long we encounter attempts to regulate the practice: a William Morgan writes in 1724 to William Beaw requesting he ‘order that no one shall practice Midwifery or Chirurgory without a Licence from the Registrar’. Yet, despite the dreadful complications, deaths, and associated mourning, flashes of joys may be glimpsed in correspondences and moments of genuine pleasure shine though. In 1761, a John Howel writes urging Richard Gough to visit when his wife, who has had a ‘jolly baby girl just born’, ‘will be out of the straw’ so they can go on excursions. Whether wife and baby daughter were included on these jaunts is not mentioned, but optimists might like to imagine they were.

Happy Christmas to all!