As the Cultures of Knowledge project and EMLO embark on the next leg of their investigative early modern correspondence journey (details of which will follow in a forthcoming blog post), it is a tremendous pleasure to announce publication this week of a catalogue set to establish itself as one of the foundation pillars of early modern transatlantic communication: that of John Winthrop the elder and his son, John Winthrop the younger.

For the final two decades of his life, John Winthrop the elder (1588–1649) served as the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Having crossed the Atlantic to New England in 1630 aboard the Arbella, John the elder proceeded to play a central role in establishing and refining the civil and religious governance of the Colony. At the time of his father’s departure for New England, John Winthrop the younger (1606–1676) remained in England for an additional year to care for his step-mother Margaret Tyndal, his younger siblings, and his own new wife Martha Fones, in addition to the family’s interests, before setting sail himself in August 1631. John the elder’s sister, Lucy (thus an aunt of the younger John), was mother of the future diplomat and financial reformer, George Downing (c. 1624/25–1684); in 1638, at the invitation of her brother, Lucy and the Downing family emigrated also to Massachusetts.

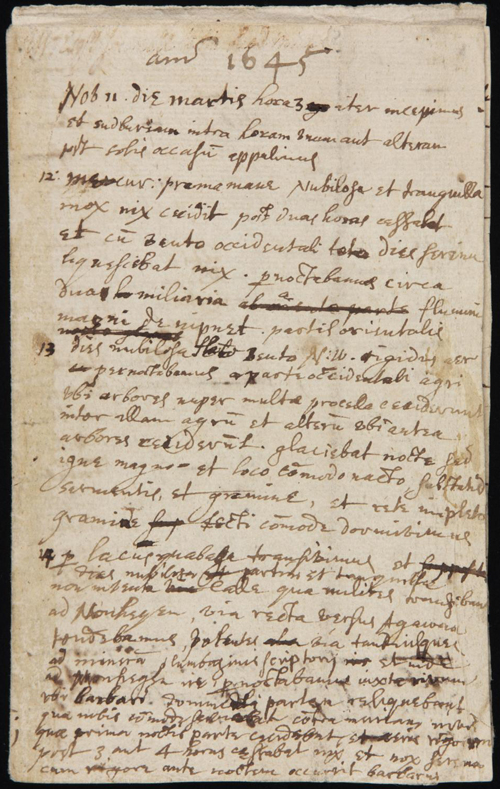

Page from an eight-page diary kept by John Winthrop the younger of a trip from Boston to Saybrook, Connecticut, and his return, November-December 1645. (The Winthrop Family Papers, General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

John the younger (who had been educated at Trinity College Dublin and had travelled extensively in Europe, progressing to the east as far as Constantinople) flourished in New England and developed there his interest in practical natural philosophy. He was an industrious and reliable correspondent — one who may be tipped to continue to ‘grow’ within the underlying networks under investigation in EMLO. From the far side of the Atlantic, he maintained a broad circle of friends and key contacts in the country of his birth. He undertook the return journey to England and stayed for a year between 1634–5, upon which occasion he was engaged by a group of puritans sympathizers — amongst whom numbered Robert Greville, second Baron Brooke; William Fiennes, first Viscount Saye and Sele; and Sir Arthur Heselrige — to establish a colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River. In honour of Winthrop’s sponsors, the name of the resulting settlement was an analgam: ‘Saybrook’.

With a strong interest in alchemy, John the younger was both friend and correspondent of the German alchemist Abraham Kuffler (1598–1657), a son-in-law of Cornelius Drebbel (1572–1633). He built up a noteworthy collection of chymical books, and conducted a correspondence with many significant European natural philosophers, including Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and Henry Oldenburg (1619–1677). In 1641, he made the long journey back once again to Europe and visited London, Amsterdam, and Hamburg, on this occasion to seek support for a venture to encourage alchemical research at a New England plantation to be called ‘New London’. The intention was that the settlement would serve as a branch of the universal college proposed by Jan Amos Comenius (1592–1670) and by those within the circle of Samuel Hartlib (c. 1600–1662); the collective aspiration was that the natural philosophers clustered in New London should work towards the perfection of their skills in such pursuits as medicine, husbandry, and metallurgy in preparation for the anticipated millennium. Upon the encouragement of Robert Child (1613–1654), the younger Winthrop seems to have sent back seeds and plant samples to John Tradescant the younger (1608–1662) for his ‘Ark’ in South Lambeth. Child requests him to send ‘some Simples, or such like to begin a firme society with John Tredislin.[1. Letter from Robert Child to John Winthrop the younger of 27 June 1643.]

The calendars of correspondence for the Winthrops published in EMLO have been based on the impressive editions produced by the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. Coupled with the letters that are converging at present in EMLO, a focus on the Winthrops and their work in New England heralds a welcome extension to the analysis of the circles surrounding Samuel Hartlib and a number of early members of the Royal Society. It is anticipated that the metadata collated for these networks in the forthcoming phase of the Cultures of Knowledge project’s work will swell and tighten. Do look out for the blog in which we will explain these plans and, in the meantime, courtesy of the links to the texts of many of the Winthrops’ letters available at the Winthrop Papers Digital Edition, please explore the archive. It is hoped that the correspondences of these two early New England settlers will establish a firm foundation upon which later transatlantic epistolary exchanges may be layered.