We are delighted to announce the award to the University of Oxford of a fourth round of funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in support of the Cultures of Knowledge [CofK] project. The grant of $393,000 will support continued work on Early Modern Letters Online and Cultures of Knowledge to the end of June 2019. Once again we are deeply grateful to the Foundation — and to all our partners, contributors, and team members — for their support and confidence in this project.

Phase IV of Cultures of Knowledge will build on work completed in Phase III to advance the collaborative development and population of Early Modern Letters Online [EMLO]. First conceived as a monolithic system designed, built, and populated in Oxford, EMLO is evolving into a central component of a distributed, transnational digital infrastructure designed, built, and populated in concert with European and international partners. In the next phase, CofK will take a further and important step forward towards this goal by disaggregating the basic components of EMLO’s letter records. The outcome will be a new set of Linked Open Data resources for tackling the complexities of early modern people, places, and dates to complement EMLO’s existing systems for handling early modern epistolary metadata.

Hitherto CofK has regarded letter records as its primary concern, and person and place records as integral components of these letter records. Yet a letter record is not elemental: accurate letter metadata rely on the accurate identification of people, places, and dates. Each of these identifications raises considerable difficulties that must be confronted if a large-scale digital infrastructure is to be firmly founded. Dating early modern letters accurately requires systems for mastering a complex landscape in which places transition between different calendars at different times. Accurately recording early modern letters requires capturing data that describes changes over time in how places are both named and nested within larger geographical entities. Confidently identifying letter writers and recipients requires the development of authority files for huge numbers of early modern individuals who are not found in national biographical dictionaries or library catalogues.

CofK’s main agenda during Phase IV will be (1) to decouple our systems for handling early modern people, places, and dates from the core system for handling letter records; (2) to define new capabilities for these systems on the basis of eight years of experience and dialogue with a wide range of partners; (3) to launch Early Modern People and Early Modern Places as free-standing, Linked Open Data resources that will be capable ultimately of being used and populated independently of EMLO; (4) to launch Early Modern Dates as a free-standing web-service able to reconcile multiple calendars; and (5) to integrate and interlink these databases with EMLO and other relevant Linked Open Data resources.

Timuctoo website at The Huygens ING

EM People, Places, and Dates will be developed in close collaboration with CofK’s partner, the Huygens ING, on the basis of a humanities-focused, Linked Data-capable IT infrastructure. EM People will be populated initially by the c. 25,000 unique early modern biographical and prosopographical person records collected thus far by Cultures of Knowledge for EMLO. EM Places will be a Pelagios-compatible, historical gazetteer with support for temporal places, drawing on the c. 5,500 disambiguated early modern place records recorded in EMLO. EM Dates will serve primarily as a web-service and API for converting across the range of early modern calendars. We are confident that the release of these new resources alongside EMLO will benefit not just Cultures of Knowledge but also a far wider community of early modern digital projects. In parallel to our central agenda, we will continue to advance and strengthen the scholarly, technical, and networking priorities we pursued during Phase III of the project.

Of these, the most important has been the regular addition of new correspondence catalogues to EMLO. In April 2015, at the beginning of Phase III, EMLO offered access to c. 61,000 letter records. Today, at the start of Phase IV, this number has doubled — EMLO provides access to c. 120,000 letter records across eighty-two correspondence catalogues. Letter records can be explored now by catalogue, theme, or contributor (with further entry points by chronology, geography, and repository in preparation), and filtered by gender. New correspondence catalogues will continue to be added to EMLO during Phase IV, albeit at a slower pace than in the recent past.

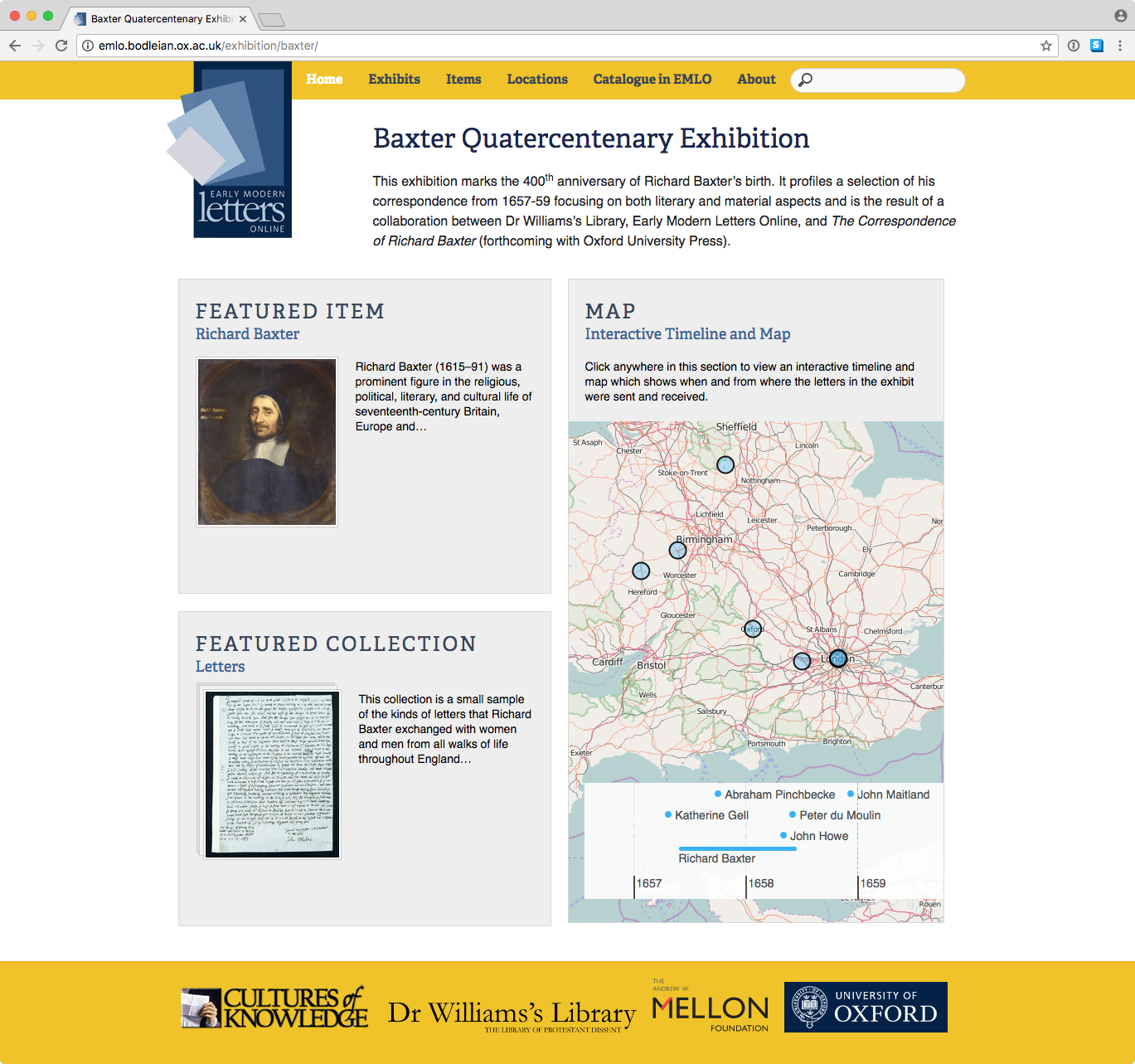

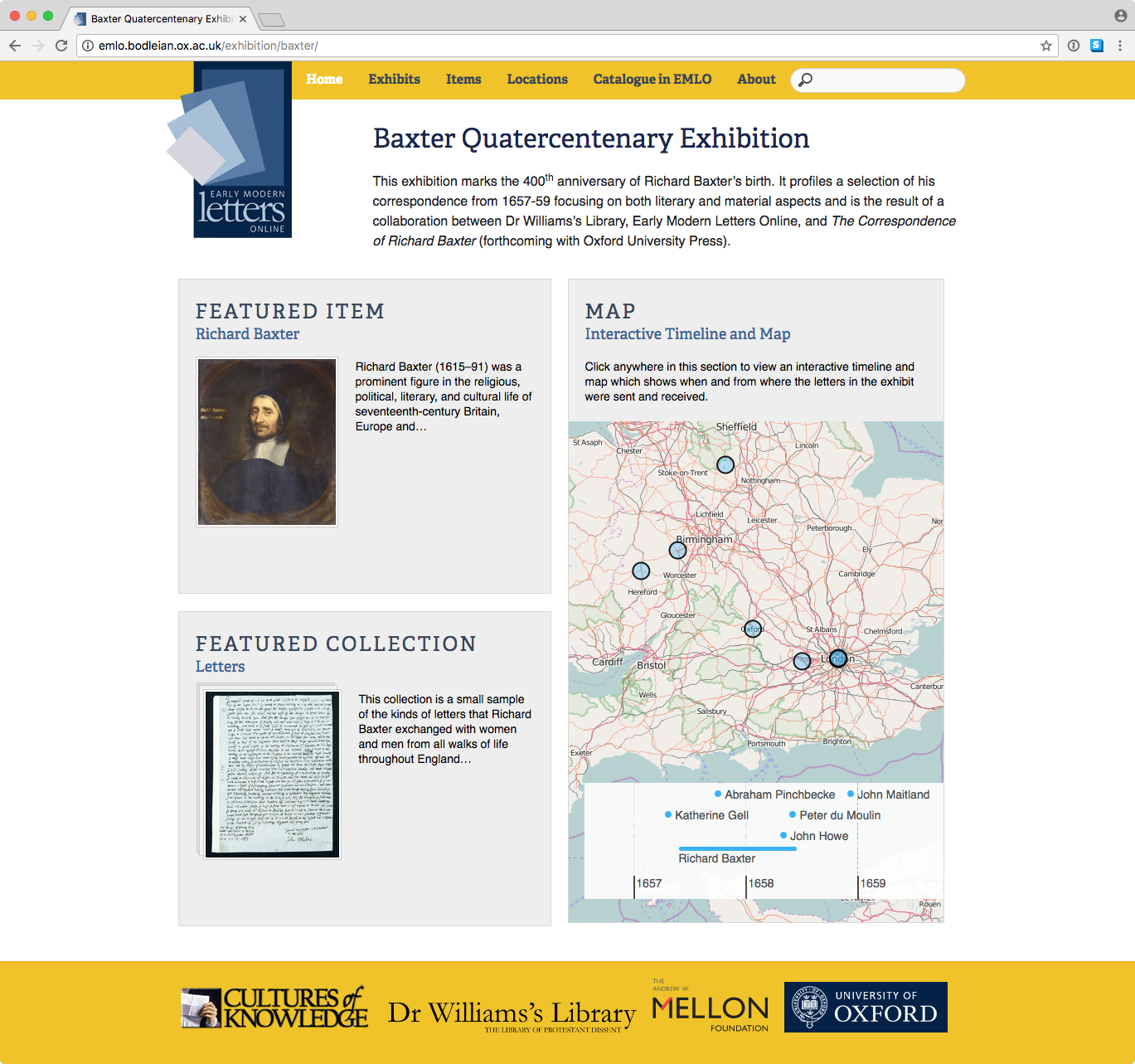

Baxter Quatercentenary Exhibition

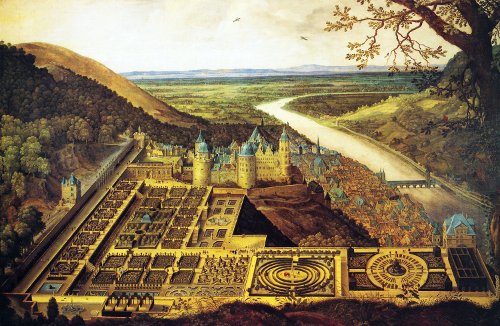

In addition to new catalogues, CofK plans to add further virtual exhibits to EMLO. Two inaugural exhibitions were created during Phase III: the Baxter Quatercentenary Exhibition marked the 400th anniversary of the birth of Richard Baxter and profiles a selection of his correspondence from 1657–9, while the second highlights the correspondences of the wives of six seventeenth-century Dutch stadtholders.

In Phase III, we made it easier for scholars and researchers to contribute letter records to EMLO by creating a custom webform for adding metadata online. This tool is already in active use by a significant number of different projects and individual contributors, including our own students at Oxford, who are learning (together with the Bodleian’s Department of Special Collections and Centre for Digital Scholarship) to transcribe manuscript letters and to contribute data to EMLO’s Bodleian Student Editions catalogue. In Phase IV we expect to continue improving the valuable disambiguation and de-deduplication tools developed in close collaboration with our partners at Aalto and Helsinki Universities.

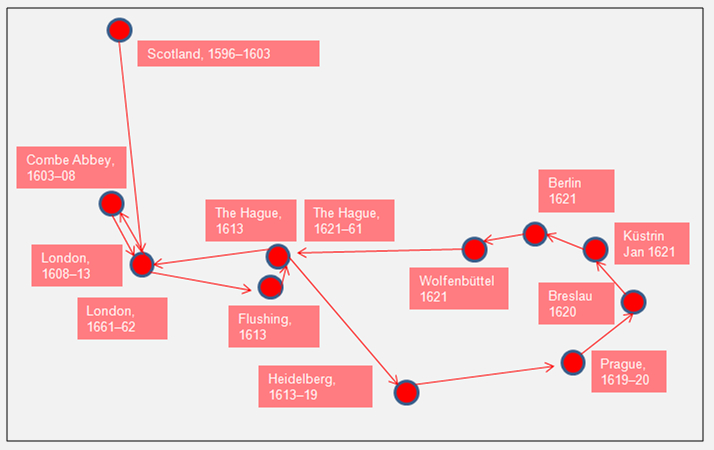

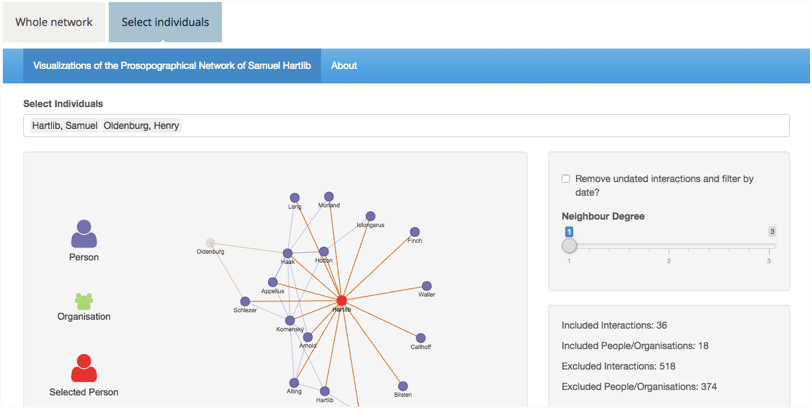

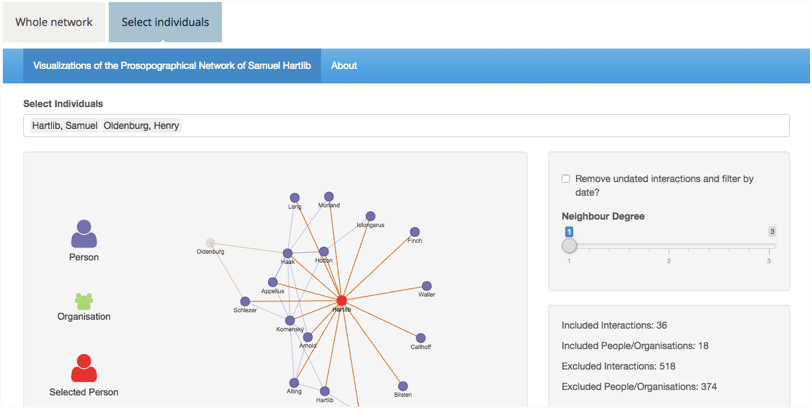

First degree connections in the prosopographical networks of Samuel Hartlib and Henry Oldenburg

We have also explored several means for exporting and visualizing both epistolary and prosopographical metadata from EMLO. One outcome of this work is a case study of the prosopographical networks of Samuel Hartlib and Jan Amos Comenius which can be viewed on the website of the Interactive Data Network group at Oxford with whom we partnered on this project. A full write-up of this project will be posted on the CofK website in the coming months. A second experimental visualization, still under construction, offers a temporal perspective on our published catalogues. In the course of Phase IV we expect to expand and intensify our activities in these areas.

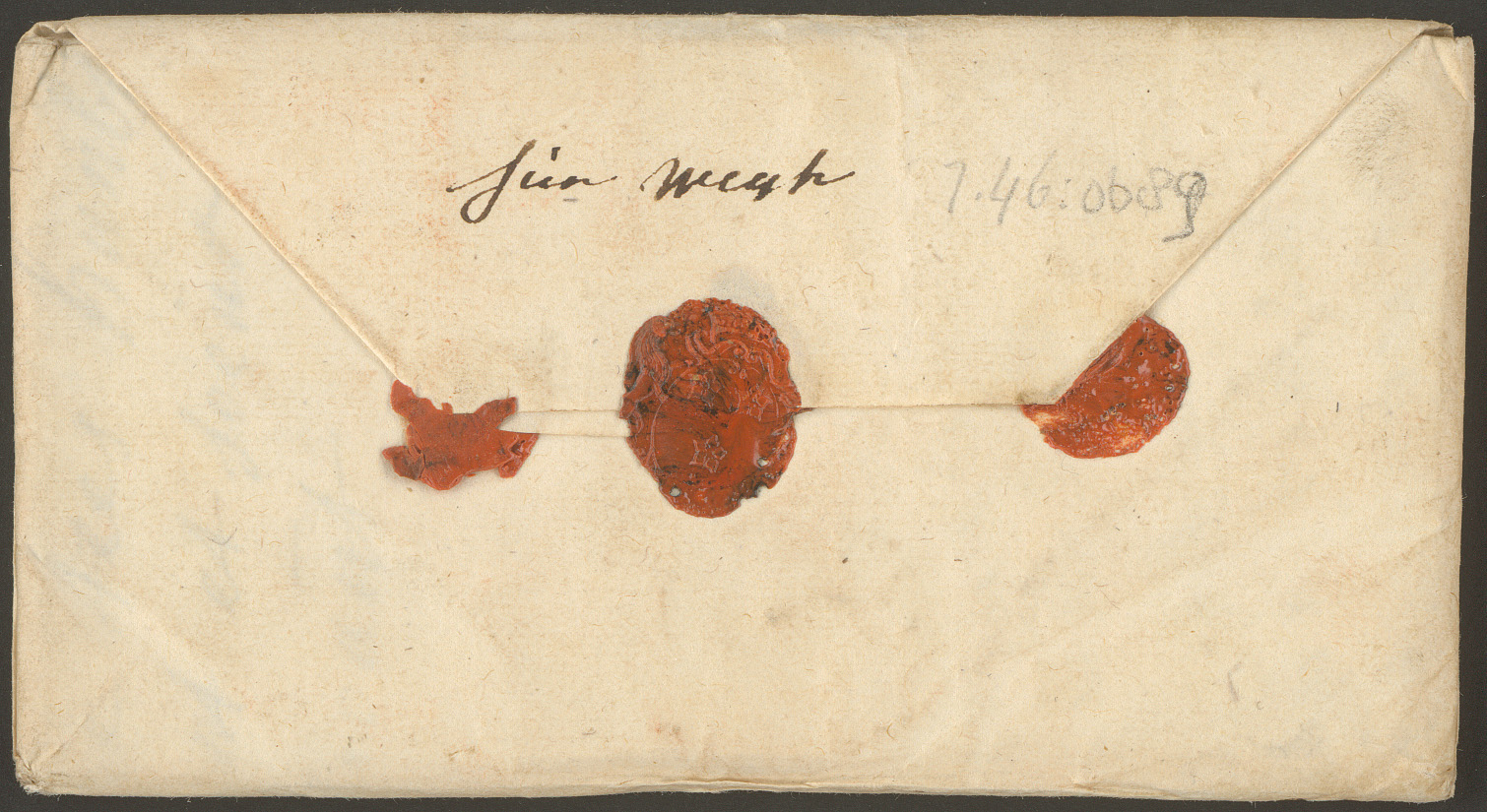

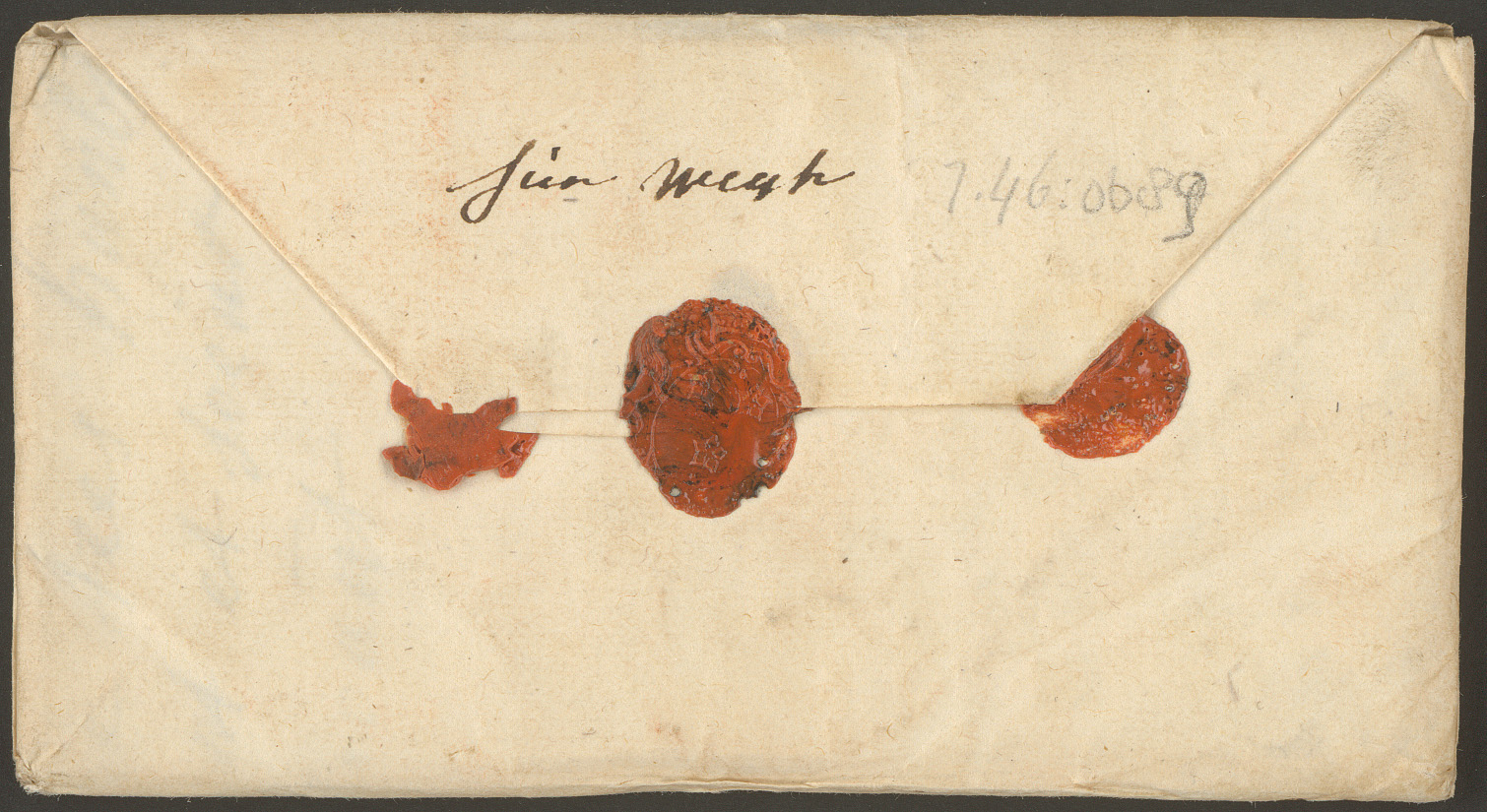

![Unopened letter sent to the marquise De Vienne in The Hague, to be handed to Gilliaume Descrote, cook to the count De Tillemette. (Museum voor Communicatie [MvC], The Hague; Brienne Collection, DB-0689)](https://www.culturesofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DB-0689_01.jpg)

Unopened letter sent to the marquise De Vienne in The Hague, to be handed to Gilliaume Descrote, cook to the count De Tillemette. (Museum voor Communicatie [MvC], The Hague; Brienne Collection, DB-0689)

In conjunction with our development of EM People, EM Places, and EM Dates, we plan to organize a small number of focused workshops for invited scholars, librarians, and researchers to review the capabilities of these databases. In Phase III, we hosted the members of the

Signed, Sealed, and Undelivered project for a workshop on

letter-locking and to develop metadata standards to record the unique characteristics of the

Brienne Collection in EMLO. In fact, we have been very fortunate, throughout Phase III, to be able to draw on a wide network of established experts and early career scholars to help advance our work. This was made possible under the auspices of the EU COST Action IS1310,

‘Reassembling the Republic of Letters’, also chaired by Howard Hotson. The COST Action has allowed us to meet regularly with scholars, librarians and archivists, IT specialists, and designers to exchange ideas and prepare shared standards for what we hope will emerge from EMLO: a state-of-the-art, transnational, distributed digital infrastructure for early modern correspondence. We look forward to participating in several more such exchanges before the COST Action completes its work in the summer of 2018 with the publication of a volume documenting its recommendations.

We hope this brief summary offers an introduction to the main goals for the next phase of our project, while highlighting the many areas of continuity from Phase III. Please do be in touch to share your feedback and ideas about these plans — we value your feedback greatly. To keep up to date with the latest news and updates from Cultures of Knowledge, please follow us on Twitter (@cofktweets), sign up to our (low traffic) mailing list or contact us directly at our project office: Cultures of Knowledge, History Faculty, University of Oxford, George Street, Oxford, OX1 2RL, U.K.; tel. +44 (0)1865 615026.

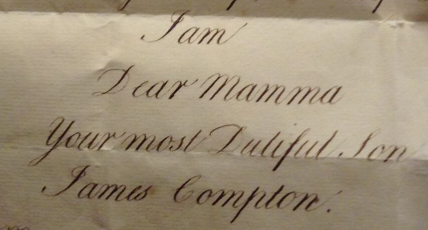

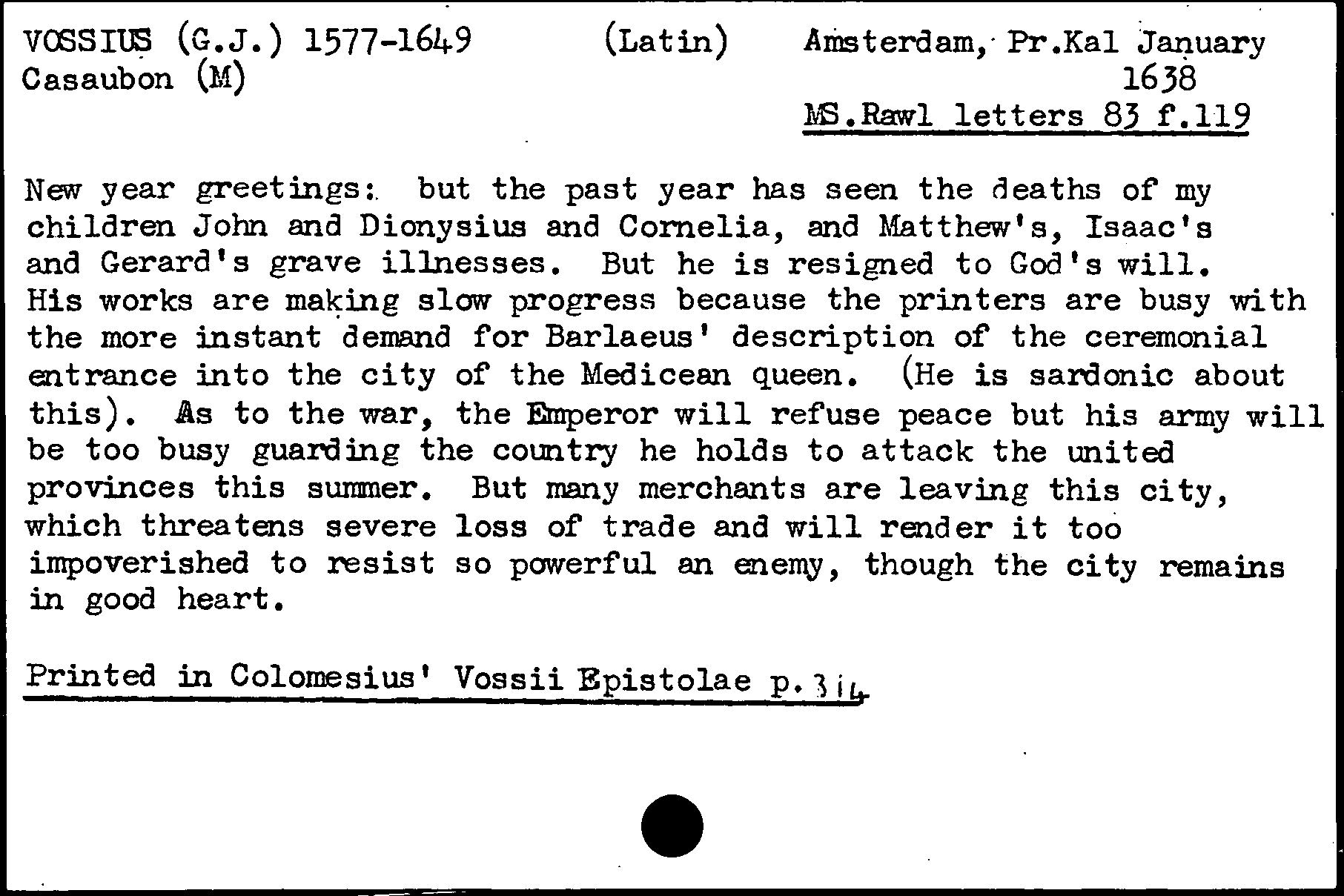

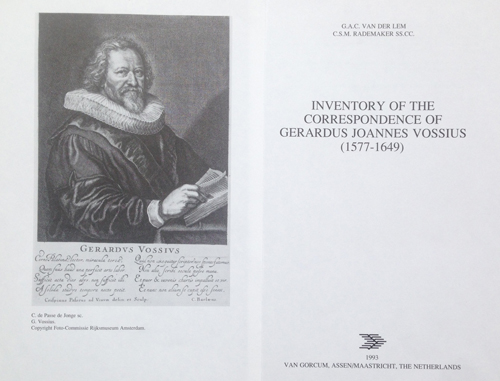

Vossius comes across loud and clear in his correspondence not only as a significant scholar but also as an exceptionally kind and caring individual and family man. When starting working with Bodleian card catalogue records six years ago, it struck me how often and how deeply this man mourned the deaths of those he loved — members of his family and his children, his friends — as well as how he sympathized with and sent comfort to a wide range of correspondents as they struggled to endure similar sorrow and bereavement.

Vossius comes across loud and clear in his correspondence not only as a significant scholar but also as an exceptionally kind and caring individual and family man. When starting working with Bodleian card catalogue records six years ago, it struck me how often and how deeply this man mourned the deaths of those he loved — members of his family and his children, his friends — as well as how he sympathized with and sent comfort to a wide range of correspondents as they struggled to endure similar sorrow and bereavement.

![Unopened letter sent to the marquise De Vienne in The Hague, to be handed to Gilliaume Descrote, cook to the count De Tillemette. (Museum voor Communicatie [MvC], The Hague; Brienne Collection, DB-0689)](https://www.culturesofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DB-0689_01.jpg)