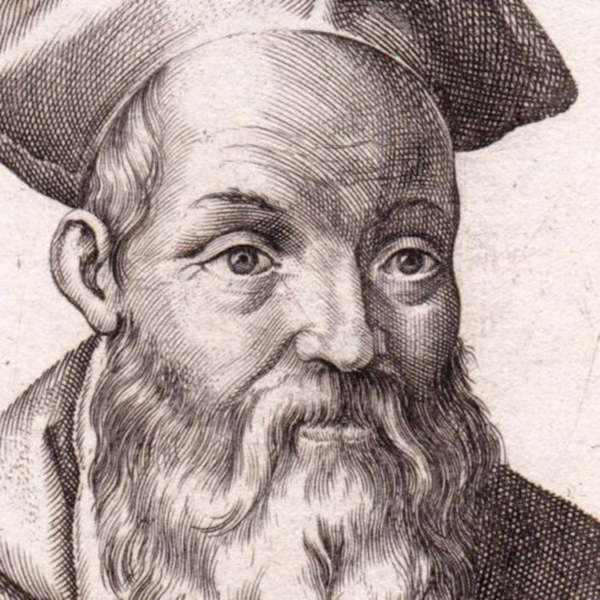

It is a joy to announce, four hundred and eleven years to the day following the poet’s birth, that the catalogue of correspondence of John Milton (1608–1674) is available for consultation in EMLO. The first correspondence to be compiled by a member of the Networking Archives project, Dr Esther van Raamsdonk (the team’s current Research Associate based at the Queen Mary University of London), this inventory is in the process of being augmented with detailed metadata and expanded.

It is a joy to announce, four hundred and eleven years to the day following the poet’s birth, that the catalogue of correspondence of John Milton (1608–1674) is available for consultation in EMLO. The first correspondence to be compiled by a member of the Networking Archives project, Dr Esther van Raamsdonk (the team’s current Research Associate based at the Queen Mary University of London), this inventory is in the process of being augmented with detailed metadata and expanded.

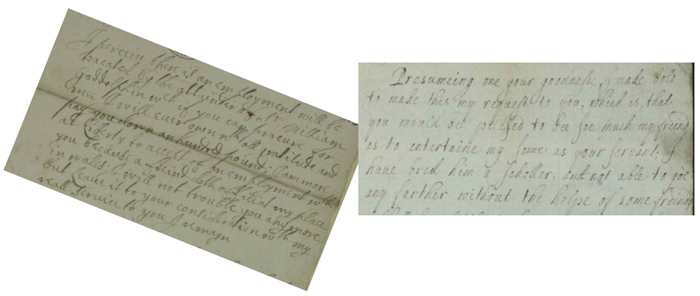

Milton’s personal correspondence survives as a body of—at present—just fifty-nine letters. Of these, approximately two-thirds were authored by the poet himself. In his final and sixty-sixth year, Milton published a volume containing a collection of thirty-one of his private letters,[1. John Milton, Joannis Miltonii Angli, Epistolarum Familiarium Liberunus … (London, 1674).] and it is this edition that has formed the basis of EMLO’s catalogue. A couple of ‘ghost’ letters for which no print or manuscript version remains have been included; these were listed by A. Rupert Hall and Marie Boas Hall in their edition of Oldenburg’s correspondence,[2. The Correspondence of Henry Oldenburg, ed. A. R. Hall and M. B. Hall, 13 vols (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; London: Mansel; London: Taylor & Francis, 1965–86), vol. 1 p. 32.] alongside two further letters from Oldenburg to Milton for which manuscripts (one a draft, the other a copy) survive in the Royal Society LIbrary.[3. Ibid., pp. 108–09 and pp. 140–1.]

Milton is known to have retained copies of the letters he composed during the interregnum when in the employment of the State as ‘Secretary for Foreign Tongues’, a role which involved preparing international diplomatic correspondence in Latin. These letters were published in 1676, just two years after the poet’s death.[4. John Milton, Literae pseudo-senatûs Anglicani Cromwellii reliquorumque perduellium nomine ac jussu conscriptae a Joanne Miltono (Amsterdam and Brussels, 1676). The metadata that describes these letters will be added to the correspondence catalogue in the course of 2020 once Esther van Raamsdonk has embarked upon her British-Academy-funded research at the University of Warwick.] Given Milton removed these manuscript copies and preserved them in his possession throughout the decades following the Restoration, it is curious that no further correspondence, neither incoming to nor outgoing from the poet, survives. Whether Milton followed Thomas Hobbes’s example of destroying a selection of his papers for fear of investigation is not known.[5. See Noel Malcolm’s introductory page to ‘The correspondence of Thomas Hobbes’, published in Early Modern Letters Online, 19 December 2017.] However, the presence of a draft and a manuscript copy of two of Oldenburg’s letters to Milton, both of which appear to have been sent, indicates that the latter’s archive of incoming correspondence has not survived.

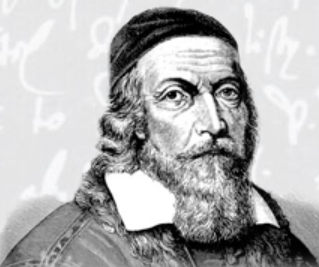

Richard Jones, third viscount and first earl of Ranelagh (1636–1712), c. 1700. (Natural Trust Collections, Attingham Park, see: <http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/609016> )

As the number of letters increases in EMLO, one of the pleasures of working with the union catalogue is to witness first-hand the plethora of connections settling into place. Milton worked as a tutor. Among his pupils was Richard Jones (1641–1712), the eldest son of Arthur Jones, second Viscount Ranelagh (d. 1670) and Katherine Jones (1615–1691), the daughter of Richard Boyle, earl of Cork and the sister of Robert Boyle. This young nobleman travelled to France in the care of none other than Henry Oldenburg, who worked as a tutor in the years following his arrival in England. The pair visited Saumur, where Milton advised his former charge in a letter of 1 August 1657: ‘I would not have you drink too deep of the wine of Saumur, which you hope to enjoy, unless you are careful to dilute the vintage of Liber with a more liberal measure of water from the Muses’ spring, in the proportion of more than five parts to one. But you have the best of advisers [Oldenburg] on this subject, and do not need a word from me. You will find it it to your own best interest to obey him …’.[6. See the letter from Milton to Jones of 1 August 1657.] Milton knew his former pupil well, having previously advised him with regard to a library that ‘unless it enables the students to improve their minds by the best instruction, it would deserve the name of ‘book repository’ rather than of “library”. You are very well aware that for this reason the desire to learn and habits of industry must be added to all these advantages.'[7. See the letter from Milton to Jones with the inferred date of May 1656.]

Richard Jones, who engaged in English politics in the 1670s, married Elizabeth (d. 1695), the daughter of Francis Willoughby, Baron Willoughby of Parham; Elizabeth’s sister, Frances, married William Brereton, third Baron Brereton (1631–1680) of Brereton Hall, who played an important role in the years following the death of Hartlib in March 1662.[8. See Leigh T. I. Penman, ‘Omnium Exposita Rapinæ: The Afterlives of the Papers of Samuel Hartlib’, Book History, 19 (2016), pp. 1–65.] Both Brereton and Jones became original fellows of the Royal Society and were elected in April and May 1663 respectively, the latter on the same date as his uncle, Robert Boyle.[9. 20 May 1663.] Jones was expelled from the Society in 1682 however, and, whatever Milton and Oldenburg taught their pupil, it was not a consummate skill in accountancy, for he ended his days surrounded by allegations of corruption and financial mis-dealings.[8. See C. I. McGrath, ‘Jones, Richard, earl of Ranelagh‘, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, version published online 3 January 2008 (requires consultation via a subscribing institution).]

Milton’s small but intriguing catalogue of letters sheds light on some of his Italian and Greek (amongst others) connections. And it provides us with tantalising glimpses into what Milton was reading, into his role as a tutor, and, more widely, the circles of which he formed a part.

Happy Birthday, John Milton!