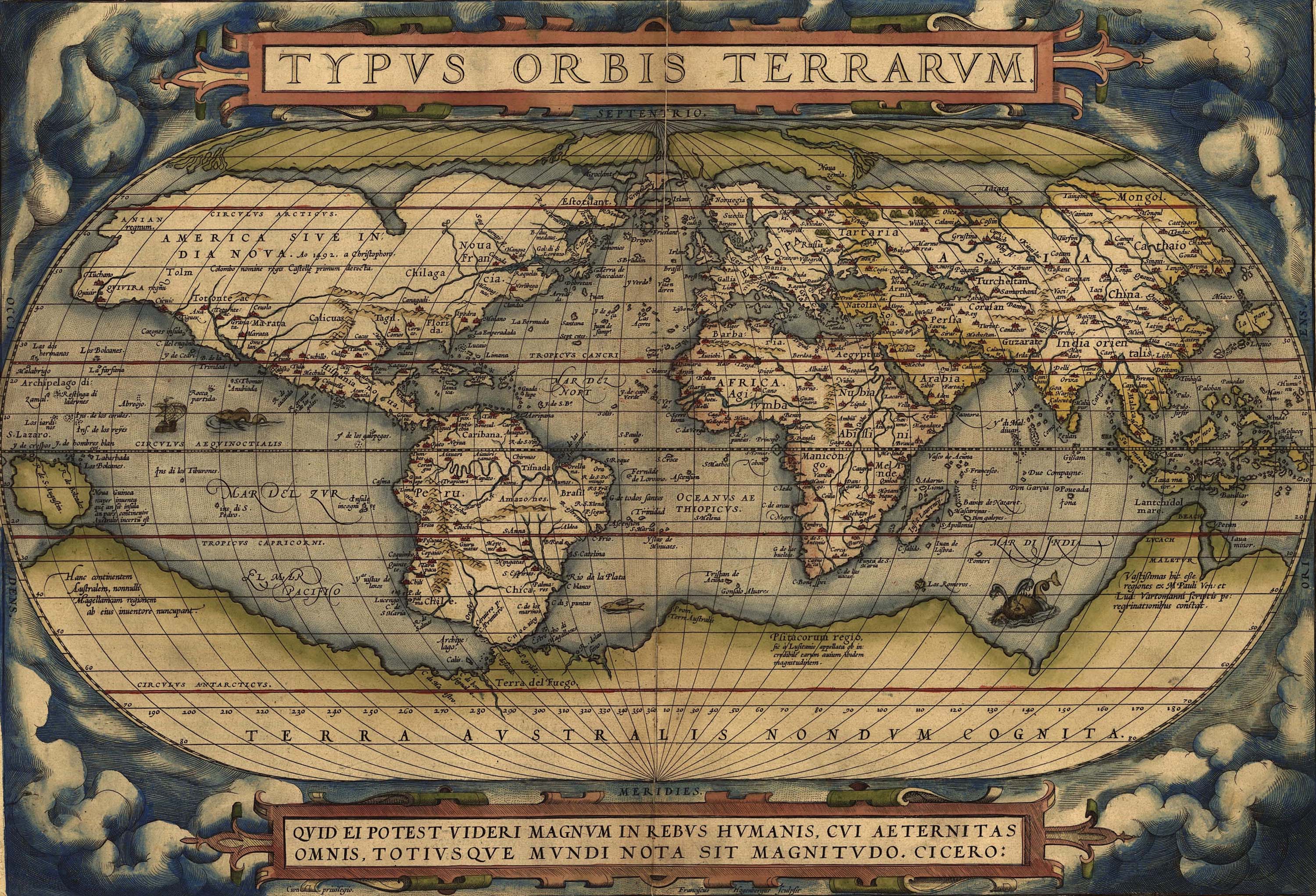

‘Typvs Orbis Terrarvm’, by Abraham Ortelius. 1570. (The Library of Congress; source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

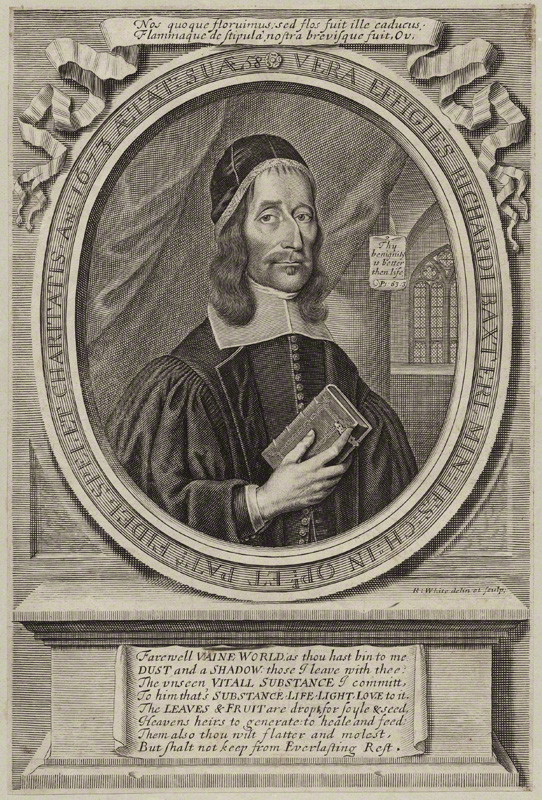

Abraham Ortelius, who thanks to his Theatrum orbis terrarum, is best known as the author of what is described frequently as ‘the first modern atlas’, was an extensive traveller: the son of an Antwerp merchant, he journeyed through the Low Countries, France, Italy, Germany, and crossed the channel to England, from where he moved on west to Ireland. Back in Antwerp, he began to compile and publish his own maps, starting with a wall map of the world and continuing with maps of ancient Egypt; the Roman empire; Asia; and Spain. In 1573, Philip II conferred on him the honour of the title of ‘his majesty’s geographer’, and today EMLO is truly delighted to be publishing Ortelius’s catalogue of correspondence.

Fittingly, but to the intense frustration of early modern historians, the story behind the after-life of Ortelius’s correspondence is composed of travel and movement as well. Ortelius became one of the leading humanists of the Low Countries and was in communication with a large number of the leading European intellectuals of his day; some decades after his death in 1598, the bulk of his correspondence ended up in the custody of the Dutch Church in London, possibly as the result of a bequest from his nephew, Jacobus Colius the younger. There the letters remained safe and sound until 1862 when the remaining nave of Austin Friars, the Dutch Church in question, was destroyed by fire. Thankfully the letters were saved and were deposited in the Library of the Corporation of the City of London at the Guildhall. From there, at the end of 1884, they were relocated temporarily to Cambridge University Library to allow Jan Hendrick Hessels to prepare his edition for publication. Disaster befell the (now reconstructed) Dutch Church once again when, during an air raid in 1940, a German bomb razed it to the ground. To fund rebuilding work, Ortelius’s letters were dispatched for auction and sold through Sotheby’s, London, to an American collector, Dr Otto Fischer, who rehomed them in Detroit. A second sale was held, back again in London with Sotheby’s in 1968, as a result of which the letters were well and truly scattered across the face of the globe. Since 1992, Ortelius scholar Joost Depuydt, an archivist at the FelixArchief [City Archive], Antwerp, has worked meticulously to track down and reunite them virtually, and to add more letters which were not published by Hessels. The fruits of his ongoing research are now to be found here in EMLO and in an article in the current issue of Imago Mundi.

As with all the catalogues we are bringing together in EMLO, it is hoped very much that as further letters come to light these will be brought to our attention so the scholars who work on the relevant correspondence may be contacted and fresh metadata added. This is one of the joys of online publication: a catalogue need not be set in stone and letters may be inserted when and as they are verified. Both Joost Depuydt and EMLO would be extremely grateful, therefore, if scholars and archivists worldwide could keep their antennae charged and should additional letters to or from Ortelius surface be in touch. Naturally, all who contribute in any way will be credited in full. Last week I found myself writing about shadowy figures and missing portraits; this week we’re on the trail of letters, for it is only with the help of the scholarly community worldwide that we will be able to reassemble as completely as possible, letter by letter, our early modern correspondences and thus piece back into existence the networks of people that sit behind and within them. So, if on your travels, you encounter stray letters of ‘his majesty’s geographer’, please let us know …

by

by