‘Christophe Plantin’, by Hendrik Goltzius. 1580s, engraving. (Source of image, Wikimedia Commons)

The catalogue published in EMLO this week — a calendar of the correspondence of the late-sixteenth century printer Christophe Plantin — is symbolic on a number of levels. Self educated and with little by way of privilege or influential contacts behind him, Plantin made his way from France to Antwerp, where he set up his printing press and worked to develop a business, the Officina Plantiniana, that expanded to become the largest typographical firm in Europe. Plantin was talented. In decades that experienced exceptional political and religious turmoil in the Spanish Netherlands, he negotiated successfully to publish works by both Protestants and Catholics alike. With judicious foresight, he opened and maintained (alongside his headquarters in Antwerp) offices in Leiden and Paris, and he developed a publishing empire that was able to continue seamlessly under the direction of his sons-in-law after his death. Indeed, the descendants of Jan Moretus, who ran the Antwerp branch, continued in business until the second half of the nineteenth century.

This calendar of his correspondence has been created from the invaluable nine volumes edited by Max Rooses (of Corpus Diplomaticus Rubenianum fame, on which EMLO’s Rubens catalogue is based) and Jan Denucé. These two editors were consecutive curators at the Museum Plantin-Moretus, in Antwerp, where the family’s and firm’s archive is housed. The catalogue in EMLO is a collaborative work, and I’m proud to say that a large number of Digital Fellows (amongst whom number postgraduate and undergraduate students, librarians, editors, translators, and interns), as well as scholars visiting the Cultures of Knowledge project and work experience students, have rolled up their collective sleeves to enter this metadata as part of their initial training with the union catalogue. It has been a joy to be involved with Plantin’s catalogue and to see this calendar of his letters come into being, and all involved deserve tremendous credit.

Plantin’s letters afford an extraordinarily detailed insight into the workings of an early modern printing house, including its day-to-day business and pan-European negotiations. They provide, furthermore, an example of a man who found a way to succeed against the backdrop of military intervention and the religious and political struggles that became the hallmark of his age. Antwerp was an important centre of humanism, and Plantin corresponded with many leading individuals, including the renowned scholar Justus Lipsius, whose oeuvre the press printed. The two men were close friends, and Plantin kept a room where Lipsius could live as he worked to correct his proofs. Known now as the ‘Justus Lipsiuskamer’ or ‘chambre Lipsius‘, this may be visited at the Museum Plantin-Moretus.

In today’s times of trouble, Plantin’s letters provide reassurance that it is possible for scholars, publishers, editors, technicians, and librarians from across Europe to come together, just as we do at present through the COST Action ‘Reassembling the Republic of Letters’ to study and discuss the intricate networks of our early modern individuals whose correspondences transcended many boundaries. This twenty-first century community is emerging as an electronic republic in its own right, and there is a satisfying symmetry to be found in the echo of the principles that underpin the correspondences of those whose lives and interconnections we work with such painstaking care to reassemble. This week’s publication in the union catalogue contains at its heart a glimmer of hope that we are able to draw together as partners, as well as proof that we work to share our developments, our workflows, and our standards. It demonstrates how we are able to unite and, here at EMLO, we are truly delighted to announce that thanks to a collaboration with, and the generosity of, the scholar and editor Dr Jeanine de Landtsheer Christophe Plantin’s catalogue is to be followed very shortly by one for his valued friend, none other than the humanist Justus Lipsius.

In a week during which the editing of scholarly correspondence rises to the fore in Oxford, EMLO is delighted to announce publication of a catalogue of the correspondence of

In a week during which the editing of scholarly correspondence rises to the fore in Oxford, EMLO is delighted to announce publication of a catalogue of the correspondence of

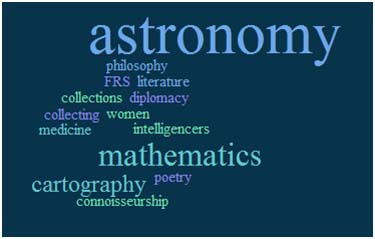

With EMLO growing so rapidly, thanks in no small measure to the generosity, altruism, and meticulous and painstaking work of such scholar-contributors as Professor Mosley, EMLO is in a position to begin listing catalogues by theme, as well as by individual correspondent. Thus from this point forward, under the

With EMLO growing so rapidly, thanks in no small measure to the generosity, altruism, and meticulous and painstaking work of such scholar-contributors as Professor Mosley, EMLO is in a position to begin listing catalogues by theme, as well as by individual correspondent. Thus from this point forward, under the