The focus of the most recent catalogue to be published in EMLO — theologian Johannes Coccejus — may be best known for the conflict into which he was drawn by the Utrecht-based theologian Gisbertus Voetius and his followers, but I’d like to highlight today how Coccejus’s afterlife contains an extraordinary episode entirely in keeping with his peace-loving character.

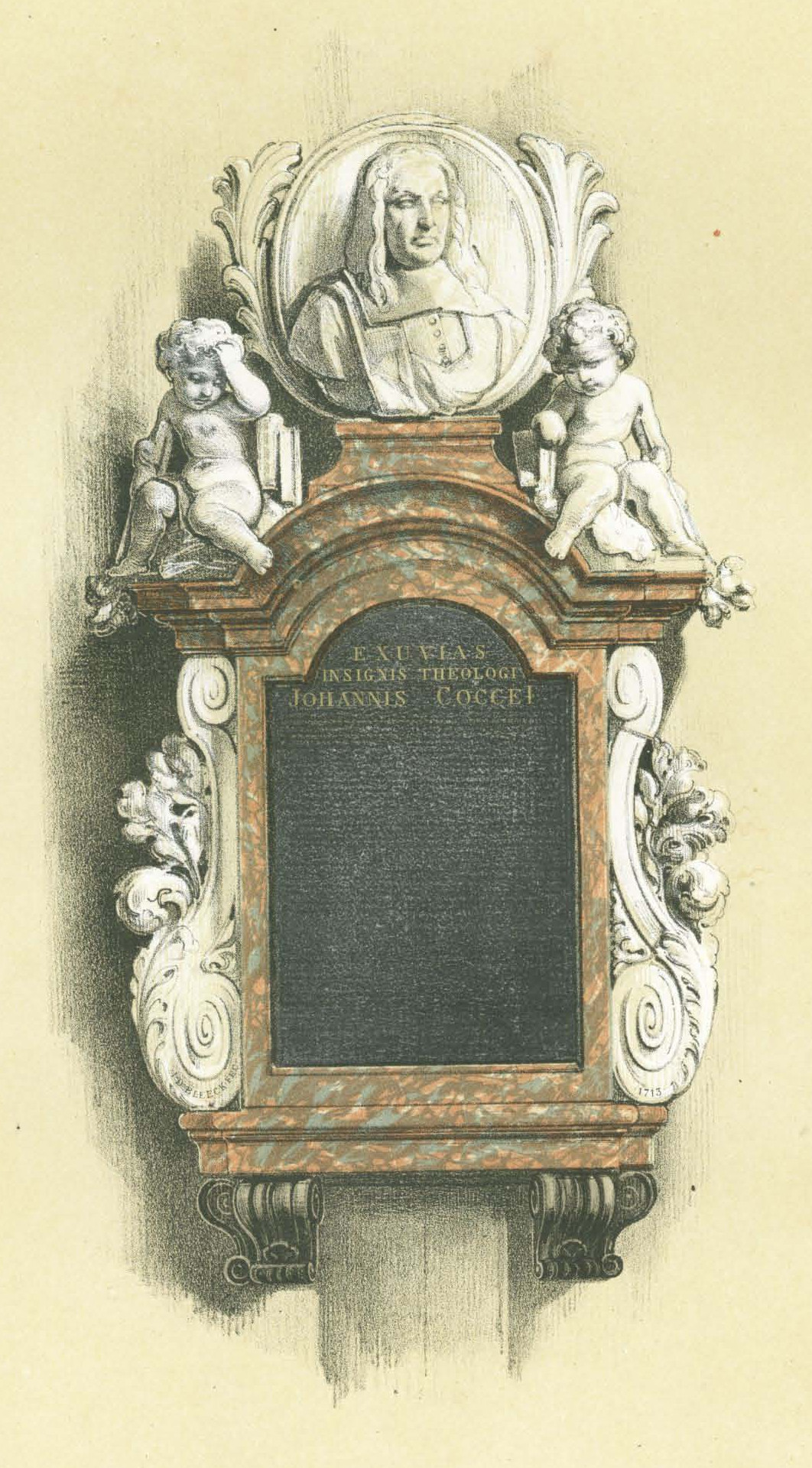

Coloured engraving of the monument to Johannes Coccejus in the Pieterskerk, taken from K. J. F. C. Kneppelhout van Sterkenburg, ‘De gedenkteekenen van de Pieterskerk te Leyden’ (Leiden, 1864), p. 113. (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

Although Coccejus (or Cocceius) was German by birth — he was born and raised in Bremen — he spent most of his adult life in the low countries. An eminent scholar, he become professor of Hebrew and oriental languages at Franeker from 1636, and from 1650 until his death in 1669 was professor of theology at Leiden. The late Willem van Asselt (who was professor of Reformed Protestantism at the university of Utrecht and professor of historical theology at the Evangelical Theological Faculty in Leuven) portrays Coccejus as: ‘a man of a deep personal faith and piety. His students observed this and one of them wrote: “His hearers noted that his eyes would fill with tears when, in giving an exposition of Scripture, he praised the richness of God’s grace”.’ It seems Coccejus was an unwilling (this noted by van Asselt) combatant in the Voetian dispute, which centred around the interpretation of the Sabbath and the Fourth Commandment, and on interpretations of salvation in the Old and New Testaments. This debate, which arose and took hold in the middle of the seventeenth century in the United Provinces, continued far beyond Dutch national borders and long after the deaths of the major protagonists.

Coccejus fell victim to plague in Leiden. He was buried in the Pieterskerk. And it was here, where the memorial erected to him still stands, that he provided from the grave scholarly refuge and shelter in a way he could never have foreseen. In 1940, as Nazi troops entered the city, the curators of the University of Leiden took the symbolic treasures of the institution — the keys, the seals, and the sceptres — and hid them in Coccejus’s tomb. Even the register of students used in graduation ceremonies was tucked in for safe-keeping with the theologian’s remains. There’s something gloriously apt about Coccejus proving himself — again in van Asselt’s words — a ‘defender of academic freedom and the Reformed tradition’ almost three centuries after his death.

Postcard of the Pieterskerk, Leiden. (source of image: Wikimedia Commons)

The calendar of correspondence you’ll find now in EMLO spans Coccejus’s scholarly life and is based on the metadata of his letters printed in epistolaries that have been collated by Monika Estermann in her invaluable inventory of German correspondence. This is another catalogue we are incorporating into EMLO in the expectation that scholars will find it of use and will be tempted to contribute additional metadata. If you’d like to add to the calendar, please be in touch.

The Library has generously made available digital images of the manuscripts, and users will find links to these from each letter record in EMLO. Dr Gordon has included metadata from the earlier researches of James D. George (1906–1977), a former secretary of

The Library has generously made available digital images of the manuscripts, and users will find links to these from each letter record in EMLO. Dr Gordon has included metadata from the earlier researches of James D. George (1906–1977), a former secretary of  to bring together students, curators, digital experts, and original manuscripts. The aim is to produce student-curated catalogues of hitherto unpublished letters. Undergraduates and postgraduates are invited to attend standalone sessions in a series of workshops at the

to bring together students, curators, digital experts, and original manuscripts. The aim is to produce student-curated catalogues of hitherto unpublished letters. Undergraduates and postgraduates are invited to attend standalone sessions in a series of workshops at the