It has been a packed year for EMLO with a score of new correspondence calendars published, innumerable updates to existing catalogues, a host of academic visitors welcomed to and working within the project, and a plethora of presentations delivered around the globe by members of the Cultures of Knowledge team. Even through this late-December break, work continues with the union catalogue’s weekly refreshes of new metadata either as updates to existing records, or — as most recently for Juan Luis Vives (1493–1540) — with the publication of a new correspondence calendar.

Vives, the Spanish humanist who was both a friend and correspondent of Erasmus, has long been one of the early modern figures whose correspondence is a desideratum for calendaring within the union catalogue, and when EMLO was approached by doctoral student Cristina Erquiaga Martínez from the University of Salamanca with the suggestion that she work with EMLO to facilitate and extend her own research, his correspondence was selected to help her to get to grips with, and understand the preparatory process for upload of, epistolary metadata. Vives’s circle of correspondents is large, varied, and includes humanist scholars (Budé, Erasmus, and Craneveldt), leaders of state and church (Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Philip II of Spain, and Pope Adrian VI). Vives wrote about church reform, politics, war, pedagogical reform, education, and the publication process involved with his works as he oversaw them from manuscript to print. He is known for his theological and philosophical work and his publications ranged from the early commentary, published in 1522 at the behest of Erasmus, on Augustine’s De Civitate Dei, to his De anima et vita, which appeared just two years before his death. His pedagogical works include Introductio ad sapientiam (1524); he wrote on the education of women (De institutione feminae Christianae, 1524); and on the public relief of the poor (De subventione pauperum, 1526). Vives’s exchanges with the leading scholars and political figures of his day make fascinating reading, and Cristina has included links in EMLO to a number of online resources where manuscripts, printed copies, or translations may be consulted. In particular, Vives’s letters reveal deep and lasting friendships formed over the course of a life spent far from his surviving family and native Valencia. As this catalogue heralds EMLO’s incursion into the first golden age of the republic of letters, it paves the way simultaneously for a number of significant and related correspondences to follow.

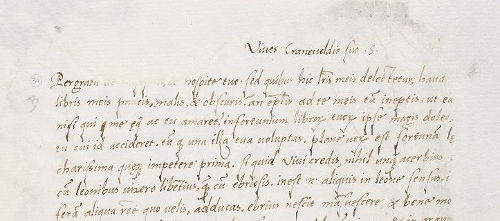

Detail of a letter written five-hundred-and-five years ago this month from Juan Luis Vives to Frans van Craneveldt. (KU Leuven, Centrale Bibliotheek BRES: Tabularium – Magazijn LC Ep. 30)

Whilst learning how to compile and prepare epistolary metadata for upload, Cristina continued her own studies on the Spanish scholar and writer Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936). Amongst Unamuno’s large circle of correspondents, many were from England, and the writer and rector of the University of Salamanca visited Oxford in the final year of his life to receive an honorary degree. In the three months she has worked with EMLO, Cristina has catalogued also the correspondence of Hernán Núñez [El Pinciano] (forthcoming, 2018), and begun work on a calendar for Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, and, whilst learning about epistolary networks, she has rolled up her sleeves and subjected Unamuno and his circles to extensive examination and visualization. We hope very much this term in Oxford has been an interesting and fruitful experience for Cristina and, whilst we’re sorry to see her return to Salamanca, we wish her well with her research and look forward greatly to following her progress. Should users of EMLO be interested to learn more about the work with correspondence underway here in Oxford and wish to enquire about visiting scholar status, an internship, or work experience, please be in touch.

It is thanks to the early modern scholarly community worldwide who write in with suggestions, corrections, and enrichments that EMLO has seen a large number of catalogue updates this past year. Among the significant additions made this autumn have been additional batches of letters to supplement the correspondences of Cheney Culpeper, Albertine Agnes van Oranje, Peter Paul Rubens, Georg Lorenz Seidenbecher, and John Worthington, while many links to increasing numbers of manuscript images becoming available online have been set in place, for example the Ortelius letters in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. This post does not signal the last update to EMLO this year — assuming technical gremlins can be kept at bay — and the team is not setting out shoes or stockings just yet: there will be more to come in the final weeks of 2017. In the meantime, however, as universities wind down and scholars prepare for Christmas and new year revels, enjoy the correspondence of Vives, EMLO, and the glories of these outbound links!