Heidelberg, which played such a crucial role in the career of Jan Gruter, the subject of my previous post, provides a setting once again as one of the cities central in the life and (mis)fortunes of Elizabeth Stuart (1596–1662). Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of James VI of Scotland and I of England and his queen consort Anna [Anne] of Denmark, and at this time of writing an exemplary critical edition of her correspondence is well on its way to completion. Based on the prize-winning PhD thesis of the Leiden scholar Dr Nadine Akkerman, the edition is published by Oxford University Press: the second volume, containing letters from the years 1632 to 1642, appeared in 2011; and the first volume, with letters from 1603 to 1631, was published in 2015. Once the third and concluding volume rolls off the press, nearly 2,000 letters to and from Elizabeth will be have been assembled from some fifty different archives and collections worldwide, and Dr Akkerman will follow her stellar edition with a biography of the Stuart princess.

Elizabeth Stuart, by Gerrit van Honthorst, 1642. Oil on canvas, 205.1 by 130.8 cm. (Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London; inv. no. NG6362)

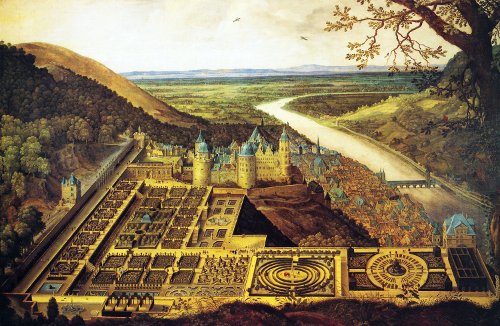

Elizabeth married the Elector Palatine Frederick V on 14 February 1613 and travelled to Heidelberg in June of that year at the age of sixteen. She lived in the city for six years before moving to Prague in October 1619, following Frederick’s ultimately disastrous acceptance of the crown of Bohemia. During this time Elizabeth and Frederick created the Hortus Palatinus, employing the French Huguenot Salomon de Caus (1575–1626), the engineer and tutor of mathematics who had worked previously for Elizabeth’s brother Henry at Richmond Palace, at Denmark [Somerset] House for her mother Anna, and for her father’s secretary of state Robert Cecil at Hatfield. De Caus’s designs for the garden were published in 1620 as Hortvs Palatinvs: A Friderico Rege Boemiae Electore Palatino Heidelbergae Exstructus, a copy of which has been digitized by the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Of course this work on Elizabeth’s garden came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, whereafter the site became a military base.

Elizabeth is known to have maintained an epistolary archive, filing both her incoming correspondence and copies of outgoing letters (an inventory was made in the 1630s by one of her secretaries, Sir Francis Nethersole). Tragically, her servant William Curtius reported that her cabinets, containing ‘rarities, books, and papers’, sustained significant water damage during Elizabeth’s final crossing from The Hague back to London in 1661. Elizabeth is known also to have destroyed much sensitive material. Indeed, she wrote to Sir Thomas Roe on 25 June 1631 that all his letters ‘are sure for the fire hath them’. EMLO is delighted to be publishing the first installment of metadata from the surviving and recorded correspondence contained in the two volumes of the edition published thus far, which cover Elizabeth’s life from her birth in Scotland, through her childhood in England, her years in Heidelberg, and her brief spell in Prague, to the first half of her exile in The Hague. Users working within a subscribing library will find that each letter record in EMLO links to Oxford Scholarly Editions Online where the relevant annotated transcription may be consulted.

Publication of this catalogue coincided with a public lecture and workshop on Elizabeth held last week at the University of St Andrews. Conceived by the University’s inspiring rector Catherine Stihler, who has nurtured a long-standing interest in Elizabeth, and shaped and hosted by Professor Steve Murdoch, the event drew together scholars to consider the character and achievements of Elizabeth as well as the momentous events and related circumstances that made up the very fabric of her life. In an impressive public lecture, Dr Akkerman debunked the persistent misrepresentation of Elizabeth as a pleasure-seeking airhead who doted more attention on her menagerie of pet monkeys and parrots than members of her own family, quoting a letter from Elizabeth to her brother Charles I in which it is abundantly clear that the ‘munkeyes’ referenced therein are none other than Elizabeth’s beloved brood of children: ‘Your honest fat henry Vane can tell you, how Hunthorst hath begunne our pictures, Where you will see a Whole table of munkeyes besides my proper self …‘.

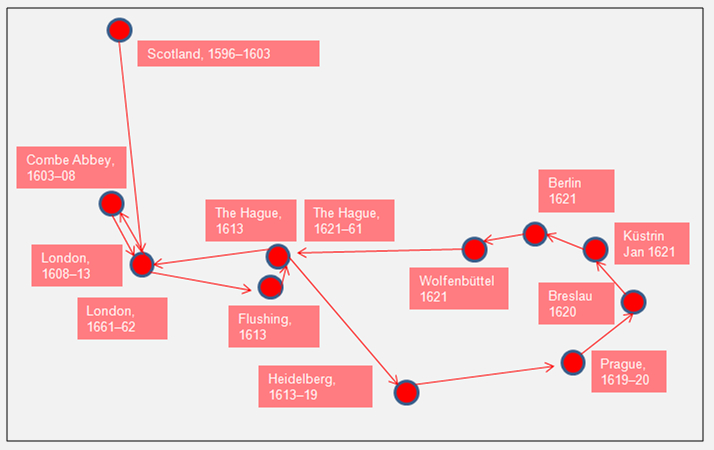

Elizabeth’s movements around Europe, 1596–1662.

Following Frederick’s death from fever on 29 November 1632 just weeks after the death at the Battle of Lützen of the Protestant leader Gustavus Adolphus, Elizabeth was left as the driving force behind the movement to restore her family to their lands. Exiled from both the Palatinate and Bohemia, she presided over a court based in The Hague for a full four decades and it is from here that the majority of her correspondence is conducted, much of it in cipher. During these years, with the momentous events of the Thirty Years’ War working out their dreadful course, and with civil war erupting in the British Isles in the 1640s and the ensuing rule of the protectorate from 1649, the threads of who was doing what, when, and where begin to get tortuously tangled. Spies abound; many of them turn out to be women. People assume aliases and are not who they profess to be. Teams of highly trained individuals assemble in Black Chambers to foil plans and unmask agents. In the tradition of many of these female spies, I shall not give anything away, but do keep an eye on Dr Akkerman’s ongoing research into the women who slipped back and forth across the seas between the United Provinces and England in the decade prior to Elizabeth’s return to London in 1661. All I will say at this point is that Nadine Akkerman and Elizabeth Stuart have a clutch of remarkable stories tucked up their collective sleeve!