Over the past three years, EMLO has been working with the inspirational AHRC-funded Curious Travellers project. Headed by Dr Mary-Ann Constantine at the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies [CAWCS], University of Wales, Aberystwyth, and Professor Nigel Leask, Regius Chair of English Language and Literature at the School of Critical Studies, Glasgow University, this research team is focussed on the writings and correspondence of the Welsh naturalist, travel writer, and antiquarian Thomas Pennant (1726–1798).

Dr Sarah Ward’s call for ‘Curious Traveller’ volunteer students.

Pennant was born and based throughout his life at his family’s estate, Downing Hall, Flintshire, in north-east Wales.[1. By his own account, Pennant was born in what was known as Downing’s ‘yellow room’: ‘I was born on June 14th, 1726, old style, in the room now called the Yellow Room; that the celebrated Mrs. Cayn, of Srowsbury, ushered me into the world, and delivered me to Miss Jy Perry, of Merton, in this parish; who to her dying day never failed telling me, Ah, you rogue! I remember you when you had not a shirt to your back.’ See Thomas Pennant, The history of the parishes of Whiteford, and Holywell (London, 1796), p. 2. The family house, Downing Hall, was damaged partially by fire in the early twentieth century, and was demolished in 1953.] With the publication of his Tours through Wales and Scotland,[2. For full bibliographic details, see the helpful list on the Curious Travellers project website.] he was responsible for capturing public imagination and engendering widespread enthusiasm for travel and early ‘tourism’ in both countries. Educated initially in Wrexham, and then at the Fulham school of Dr (or Mr) Thomas Croft — the scene of the tragic accident that took place just six years prior to his arrival, while the son of Elizabeth Compton attended the school, which resulted in the death of Dr Croft’s sister, Ann —[3. For details of this sad incident and the subsequent trial, see my blog from last year, ‘Elizabeth Compton, her son, and a Huguenot’.] the young naturalist continued his studies at Queen’s College, and then Oriel College, Oxford. Pennant’s interest in natural history had been sparked (according to his own account)[4. Thomas Pennant, The Literary Life of the Late Thomas Pennant by himself (London, 1793, p. 1; for an explanation of this curious anachronism, do consult Charles W. J. Withers’s entry on Pennant in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, published online at < https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/21860 > , accessed 31 March 2018 (this requires access from a subscribing institution); in Withers’s words, this title: ‘hints at Pennant’s sense of humour. It is signed only by dotted lines to indicate the death of the author: it is for that reason that his History of the Parishes is signed ‘RESURGAM’, with its implication of literary resurrection.’] at the age of about twelve when his relative John Salisbury gave him a copy of Francis Willughby’s Ornithology.[5. Willughby (or Willoughby), an early member of the Royal Society, was the lifelong friend and collaborator of John Ray. His Ornithology was published posthumously in 1678. Many references to his life, work, death in 1672, and subsequent posthumous publications may be found in the letters of Martin Lister; see Anna Marie Roos, The Correspondence of Dr. Martin Lister (1639–1712). Volume One: 1662–1677 (Leiden: Brill, 2015).] Although the brief of the Curious Travellers project is to concentrate primarily on Pennant’s letters of most relevance to his Tours, the team is compiling also an inventory of his complete correspondence. Thus far, metadata for the letters that reside in the care of the Bodleian Libraries, The Linnean Society of London, and the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale, have been drawn together and published in EMLO.

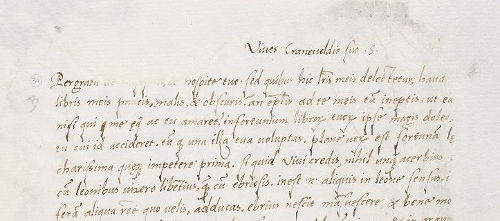

It was in the spirit of Pennant that EMLO set off ‘on the road’ once again last week to help host a workshop at the University of the West of England in Bristol, courtesy of an erstwhile EMLO Digital Fellow and current UWE member of staff, Dr Sarah Ward. A call had been circulated early in March and, within hours, twelve of Dr Ward’s undergraduate students had signed up, together with Laura Lawrence, a current EMLO Digital Fellow, to spend an afternoon working with photographic images to generate rough transcriptions of Pennant’s letters from the collections of the Bodleian Libraries, including MS. Ashmole 1822 (Pennant’s letters to the museum curator William Huddesford) and MS. Gough Gen. Top. 43 (Pennant’s letters to the antiquarian Richard Gough). Although Pennant’s handwriting and punctuation were felt to be a little eccentric at times (but thankfully Dr Constantine was on hand to help), these letters turned out to be brimful with tantalizing details of natural history specimens, including striped antelopes, various horns and fossils, five-toed lizards, and bats.

The transcriptions created by these remarkably talented students, all whom are to be credited for their contributions, will be checked and edited by the Curious Travellers team, and additional work on Pennant’s letters to Gough will be conducted in Oxford later this year when Dr Constantine takes up residence at the Bodleian as a visiting scholar (upon which occasion we hope very much that a follow-up workshop involving these wonderful students will be arranged — and, in the meantime, should anyone with an interest in Pennant wish to sign up as a volunteer transcriber, please be in touch . . . ).

Students at the Curious Travellers/EMLO/UWE workshop, Bristol, 20 March 2018.

Lias: the Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources is a peer-reviewed publication which takes its name from the Dutch work for ‘file’; it is committed to publishing primary sources that relate to the intellectual and cultural history of early modern Europe. The journal was established to provide a platform for sources that are relatively short in length. And it is in the pages of this journal that Hollis’s edition of the Elstob-Ballard correspondence may be consulted, either by subscription or through the purchase of a single hard-copy issue; and should users be within a subscribing institution, links to the downloadable text are provided from each relevant letter record in EMLO. The journal’s editor-in-chief,

Lias: the Journal of Early Modern Intellectual Culture and its Sources is a peer-reviewed publication which takes its name from the Dutch work for ‘file’; it is committed to publishing primary sources that relate to the intellectual and cultural history of early modern Europe. The journal was established to provide a platform for sources that are relatively short in length. And it is in the pages of this journal that Hollis’s edition of the Elstob-Ballard correspondence may be consulted, either by subscription or through the purchase of a single hard-copy issue; and should users be within a subscribing institution, links to the downloadable text are provided from each relevant letter record in EMLO. The journal’s editor-in-chief,

Yet gems aplenty are to be found within the correspondence, and users are encouraged either to take advantage of the subscriptions held by their institutional libraries to follow the links from each record in EMLO to the texts that are mounted in OSEO, or to locate the hard-copy volumes. The metadata for this correspondence were supplied to EMLO by

Yet gems aplenty are to be found within the correspondence, and users are encouraged either to take advantage of the subscriptions held by their institutional libraries to follow the links from each record in EMLO to the texts that are mounted in OSEO, or to locate the hard-copy volumes. The metadata for this correspondence were supplied to EMLO by

Twenty international scholarships are available and doctoral students will be invited to explore and discuss the ‘phenomenon of the Republic of Letters, its historical and theoretical manifestations, and the terminological challenges it poses’. They will be encouraged to consider such questions as the aesthetic, political, and social conditions upon which networks for knowledge exchange are built; to ask what rules and customs those communicating with each other observe; as well as to explore the transformations these communities undergo, and determine terminology and methods that might be employed to describe today’s ‘literary and intellectual landscape on a transnational scale’ ― a landscape itself now termed a ‘New Republic of Letters’ .[2.

Twenty international scholarships are available and doctoral students will be invited to explore and discuss the ‘phenomenon of the Republic of Letters, its historical and theoretical manifestations, and the terminological challenges it poses’. They will be encouraged to consider such questions as the aesthetic, political, and social conditions upon which networks for knowledge exchange are built; to ask what rules and customs those communicating with each other observe; as well as to explore the transformations these communities undergo, and determine terminology and methods that might be employed to describe today’s ‘literary and intellectual landscape on a transnational scale’ ― a landscape itself now termed a ‘New Republic of Letters’ .[2.  in Tallinn, this four-day workshop offers those who focus on early modern correspondence the opportunity to prepare epistolary metadata using tools that will both assist their own research and facilitate publication in a union catalogue. Early career scholars, representatives from institutions with large holdings of early modern correspondence, and individuals interested in disseminating further the taught epistolary standards, techniques, and tools within their scholarly communities are encouraged to apply. Whilst applications are welcomed from scholars in all countries participating in the COST Action, the Training School is funded by an ‘Inclusiveness and Target Countries’ grant, so scholars from these countries are encouraged in particular to apply (further details regarding this may be found in the original call).

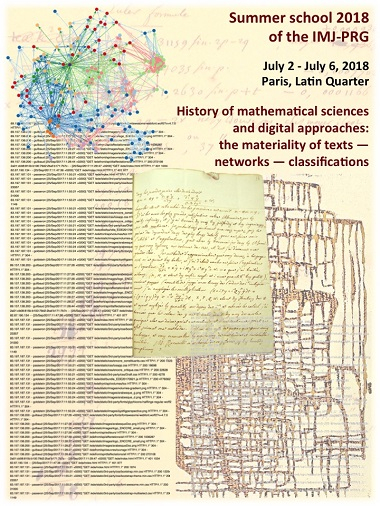

in Tallinn, this four-day workshop offers those who focus on early modern correspondence the opportunity to prepare epistolary metadata using tools that will both assist their own research and facilitate publication in a union catalogue. Early career scholars, representatives from institutions with large holdings of early modern correspondence, and individuals interested in disseminating further the taught epistolary standards, techniques, and tools within their scholarly communities are encouraged to apply. Whilst applications are welcomed from scholars in all countries participating in the COST Action, the Training School is funded by an ‘Inclusiveness and Target Countries’ grant, so scholars from these countries are encouraged in particular to apply (further details regarding this may be found in the original call). Thereafter, mathematical historians, historians of science, and digital humanists may be interested in the International Summer School being organized by the

Thereafter, mathematical historians, historians of science, and digital humanists may be interested in the International Summer School being organized by the