by Lorenzo Mancini and Martín M. Morales (Archivio della Pontificia Università Gregoriana, Rome)

Umberto Eco defined Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) as ‘the most contemporary among our ancestors, and the most outdated among our contemporaries’.[1. Umberto Eco, Il Museo del mondo (Roma, 2001), p. 14.] Over the past hundred years, scholars from many fields have studied Kircher and his works in depth, making the Jesuit polymath one of the most fascinating case studies in the early modern period. The aim of Monumenta Kircheri — a project that has been announced recently at the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University and which forms part of its new collaborative web platform Gregorian Archives Texts Editing [GATE] — is to bring together this body and tradition of research and use it to assemble a full edition of Kircher’s correspondence as well as an in-depth study of his printed works. Before describing details of the ambitious work underway in Rome, however, it is worth considering the term Monumenta and its significance in the title of this project.

From Monumenta …

Some forty years ago Jacques Le Goff (1924–2014) set out the substantial overlap between document and monument in an article published in the Einaudi Enciclopedia.[2. Einaudi Enciclopedia, vol. 5, pp. 38–48.] After reconstructing the history and evolution of both terms, the French historian concluded:

The document is a monument. That is the outcome of the effort made by historical societies — whether purposefully or not — to impose the future that given image of themselves. As a final result, there is no document-truth. Each document is a lie. It is up to the historian not to be so naive. The medievalists, who worked so hard in order to build a critique — always useful, of course — of the falsehood must overcome this issue, since any document is at the same time true — including, and perhaps especially, the false ones — and false, because a monument is primarily a disguise, a deceptive appearance, a montage. First of all, it is necessary to dismantle and demolish that montage, deconstruct that construction, thus analyzing the conditions in which those documents-monuments have been produced.

In 1894, at the time of the publication of the first volume of the Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu,[3. Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu (Madrid, 1894).] it was not possible to make such an observation, which is the result of reflection generated by historical conceptions — for example, the changing view of the document, inaugurated by the Annales school — that matured in the twentieth century. In the wake of positivist historiography, it was a foregone conclusion for the Jesuits commissioned to write institutional history to entitle a collection of sources ‘Monumenta’ with implied (but not always obvious) reference to the first collection of that type, published from 1826, the Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

The Monumenta arose from a conviction that the truth lies inside the sources. One consequence of this premise has been to gather the greatest quantity of documents so that the ‘truth’ could be as complete as possible. However, within this historiographical paradigm, the exponential growth of information became an obstacle when it came to building a historical narration, concatenating effects with causes and trying to explain the succession of events in an unequivocal way. The Monumenta was to replace writing, which got bogged down in relentless and growing complexity, with documentary series, so that others could relate the story. To that effect, this vast publishing operation announced the slow and progressive phase-out of the writing of the institutional history in an attempt to look for other ways to build the Jesuit identity. The Monumenta was intended to provide support for the writing of history and, in the specific vision of the Jesuit fathers, for the writing of the history of the Society of Jesus. Paradoxically, however, the more the sources made available in Monumenta increased, the more their primary goal seemed to recede.

The enterprise of the Monumenta began to reveal its own limitations to some of the Jesuits involved in its organization. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the release of the first volume, Dionisio Fernández Zapico (1877–1948) and Pedro de Leturia (1891–1955) noted the issues with the original project.[4. Dionisio Fernández Zapico and Pedro Leturia, ‘Cincuentenario de Monumenta Historica S.I. (1894-1944)’, in Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 13 (1944), pp. 1–61).] The hope of the Superior General Luis Martín (1846–1906), promoter of the initiative, was that the monumentalisti would simply be ‘editors, not commentators of the documents’. According to Martín, document reproduction, characterized by ‘rigorous exactitude and meticulous correction’, was a guarantee of truth and could illuminate the history of the Society. Zapico and Leturia highlighted the technical difficulties of the critical edition of the documents, where it was usually not possible to maintain the impartiality envisaged by Martín. In addition, these two Jesuits recognized the intention to duplicate what was present in the archives as a result of the desire to make the history of the Order known universally, rather than bringing light into the darkness that characterizes intrinsically archival documentation. Thus the idea of equivalence between truth and document became a more complex issue. The continuous increase of information, as already perceived by the editors of the Historia Societatis of the old Society, was even more evident in the context of the restored Society and enhanced the difficulties in achieving the necessary selection that any historiographical operation implies.

… to Monumenta Kircheri

Nowadays, proposing the term Monumenta to identify the publication of a new series of documents might appear anachronistic. Yet the global context of the historiographical system of these Monumenta is different. The use of a technological milieu, such as that adopted in GATE, leads to a different conception of the document compared to the ‘old’ Monumenta. For instance, the possibility for the reader to consult online the digital reproduction of documents de facto tends to raise the issue of the critical edition in a different light. The methods of ecdotics, which presupposes the absence of the document, needs to be rethought. Also distinctive is the conception of creating knowledge to underpin GATE, which stems from the belief that fields of knowledge have an interlinked development and assume a collaborative and discursive environment where they can flourish, whereas such a possibility was not available in, for example, the workshops of the first monumentalisti. Repurposing the tradition of the Monumenta does not mean sharing the same vision of history and of the document proposed by the monumentalisti. Rather, the primary objective of GATE is to conduct a critical analysis of the documents/monuments, as intended by Le Goff, and, therefore, of the social system that produced them.

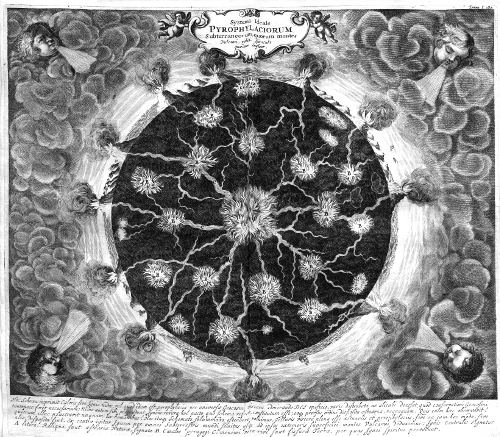

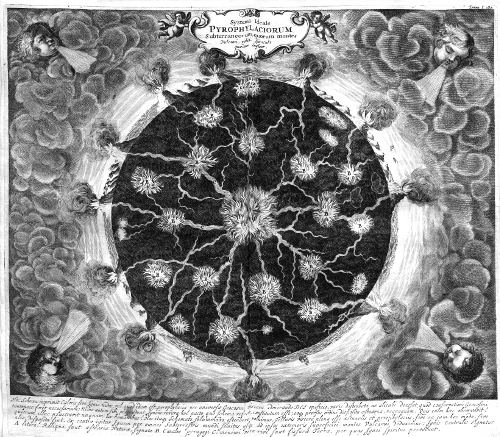

System of subterranean fires from Athanasius Kircher, ‘Mundus Subterraneus’ (1678 edition), vol. 1, p. 194. (Source of image: Wikimedia Commons and Athanasius Kircher at Stanford image gallery)

Kircher on GATE: a practical introduction to GATE and Monumenta Kircheri

GATE is a web platform based on Mediawiki, the software developed by the Wikimedia Foundation and used in all its projects, such as Wikipedia, Wikisource, and Wikiversity. Mediawiki is open source and maintained by a very active community of volunteer developers. The team at GATE chose Mediawiki for several reasons, including ease of installation; the ability to customize; its collaborative environment; traceability; and the possibility of reversing any contribution. It should be noted that a number of esteemed early modern projects have worked effectively with Mediawiki as a platform for collaborative work, including the successful Transcribe Bentham project.

GATE has two main sections: Monumenta and Collections. The first hosts Monumenta Kircheri and Monumenta Bellarmini, both of which are intended ultimately to form complete editions and enable a deeper study of the correspondence and works of Athanasius Kircher and Roberto Bellarmino. Collections consists of a group of sources related to other authors (including at present: Angelo Secchi, Balthasar Loyola Mandes, and Pasquale D’Elia) that are being made available to users. Collections contains only documents preserved by the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University; Monumenta collects, in addition, documents from from other institutions.

Through GATE, users are able to browse the digitalization of the documents; read transcriptions as these become available; consult the pages created as annotations within the texts; query the documents metadata and annotations and make full-text searches; and access the bibliography of each project. Crucially, registered users may in addition contribute to the transcription, edition, and annotation of documents; create pages about the content of the texts; add new records to bibliographies; and initiate and contribute to discussions.

Monumenta Kircheri is the section of GATE dedicated to the study of Athanasius Kircher’s works and correspondence. Kircher is being used as a case study to explore the complexities and paradoxes of a ‘long’ modernity, extending from the seventeenth century to the present day. In fact, the fundamental aim is to articulate more clearly what is often hidden in historical research, and what matters to this project lies not in the past, but rather in the present. From a methodological point of view, it is hoped the project will not be simply inter-disciplinary, but trans-disciplinary. Beginning with Kircher’s crucial role in the early modern Republic of Letters, the project will insert Kircher’s case within a larger context involving the question of the nature of knowledge as both a kind of savoir faire and a kind of savoir vivre. From this perspective, the intention is to reconsider Kircher’s vast bibliographical production and the methods of its dissemination, highlighting how Kircher grappled with, and contributed to, such concepts as novitas or curiositas. The project is concerned also with the material aspect of culture, most specifically with the early modern changes in the modes and methods of communicating and disseminating knowledge. The way in which Kircher managed, reproduced, and created knowledge is a lens through which several fundamental aspects of both the early modern and the modern world may be understood and which have been the object of a recent surge of scholarly interest, for example the exponential growth of information and consequently the development of new and more effective techniques to digest, store, and select this new body of knowledge. The starting point for Monumenta Kircheri is the Bibliographia Kircheriana, an extensive bibliography which aims to record all the publications about Kircher published since his death. At present the Bibliographia lists 641 entries and it is being updated on an on-going basis with new records provided by authors or found in other publications.

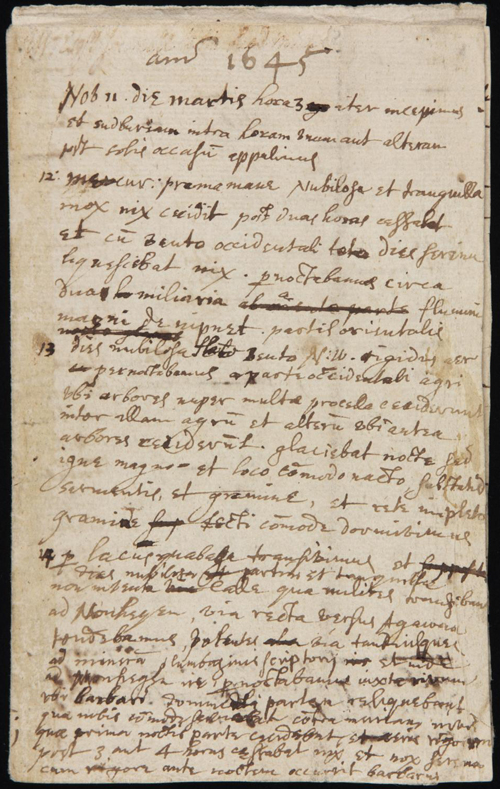

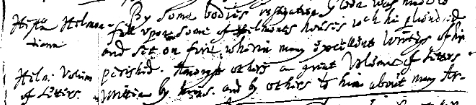

Through the transcription of correspondence and works, the intention is to create a comprehensive database of Kircher’s production which will permit investigation with a number of research questions it has not been possible to pose until now. It is hoped this database will become a valuable source not only for specialist Kircher scholars, but also for early modern historians. Transcriptions are made using GATE’s collaborative environment, where proofreading and validation of transcriptions may be easily managed. Users transcribe the text working from the image of the original manuscript or printed page. All the correspondence is being digitized again, with the aim of updating the digital images produced by Stanford in late 1990s. An edition will be assembled using a selection of TEI tags and footnotes, and with annotations as names, places, works, and objects mentioned within the texts are identified. Each annotation will connect to a specific page about that entity. Transcription, edition, and annotation are three different processes that can be contributed by different users, and while the project believes that GATE provides an excellent work environment, it welcomes also suggestions and comments regarding improvement, and it is hoped very much that members of EMLO’s community will become involved.

Call for collaboration

Being a collaborative project, GATE seeks new volunteers. Several collaborations are underway with Italian high schools, involving at the time of writing more than 150 students, who have helped to set up the Bibliographia Kircheriana and have transcribed about fifty letters from Kircher’s correspondence as well as some of his printed works. The advice and involvement of more experienced users, for example master students, doctoral candidates, and established scholars, will be appreciated in particular. Training in how to use GATE, as well as on-hand assistance during the transcription, edition, and annotation processes, will be provided. Every contribution to the project will be valued enormously, and those interested in Kircher and his work are urged to be in touch.

Having married Edward, third Viscount Conway and Killultagh (c. 1623–1683), who encouraged her wholeheartedly in her intellectual pursuits, Lady Anne had access to the family’s collection of books that formed one of the largest private early modern libraries in the country. A victim of severe ill health, she was forced to live in semi-retirement at the Conway family seat, Ragley Hall in Warwickshire but her illness introduced her, as a patient, to some of the renowned physicians of her age, including William Harvey, Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, and Thomas Willis, as well as to the ‘Irish stroker’, Valentine Greatrakes.

Having married Edward, third Viscount Conway and Killultagh (c. 1623–1683), who encouraged her wholeheartedly in her intellectual pursuits, Lady Anne had access to the family’s collection of books that formed one of the largest private early modern libraries in the country. A victim of severe ill health, she was forced to live in semi-retirement at the Conway family seat, Ragley Hall in Warwickshire but her illness introduced her, as a patient, to some of the renowned physicians of her age, including William Harvey, Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, and Thomas Willis, as well as to the ‘Irish stroker’, Valentine Greatrakes.