The fourth Bodleian Libraries Manuscript and Textual Editing Workshops is scheduled to take place this week, and I’m thrilled to announce that the metadata and transcriptions generated during the three previous sessions may all be consulted now in EMLO within the Bodleian Student Editions catalogue. As a project, we are delighted also to have been able to bring together in the Weston Library a number of our esteemed contributors and colleagues in a fascinating hands-on demonstration of letterlocking. The extraordinary workshop was led by Jana Dambrogio (Thomas F. Peterson Conservator for Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Library in Cambridge, Mass.) and Daniel Starza Smith (Lecturer in Early Modern English at KCL), and places were made available to students who had signed up for the Bodleian Student Editions’ manuscript and editing workshops and to a group of second year students from the ‘Writing in the Early Modern Period, 1550–1750’ Further Subject headed by Professor Giora Sternberg, as well as to staff from the Bodleian, CofK, and EMLO.

Letterlocking, the term coined by this dynamic and eloquent duo, who constitute an integral and invaluable part of the Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered project team, is the process of folding and securing a letter that was used before mass-produced ready gummed envelopes became de rigueur in the nineteenth century. If, when your letter was ready for dispatch, you did not employ a combination of these time-honoured techniques of folding, cutting, tying, stitching, and/or sealing, what you had written would not have remained private. As Dan explained, sending an unlocked letter four centuries ago would be like pressing the button today on emails without encryption and using accounts with no password.

Letterlocking, the term coined by this dynamic and eloquent duo, who constitute an integral and invaluable part of the Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered project team, is the process of folding and securing a letter that was used before mass-produced ready gummed envelopes became de rigueur in the nineteenth century. If, when your letter was ready for dispatch, you did not employ a combination of these time-honoured techniques of folding, cutting, tying, stitching, and/or sealing, what you had written would not have remained private. As Dan explained, sending an unlocked letter four centuries ago would be like pressing the button today on emails without encryption and using accounts with no password.

Jana and Dan taught the assembled company how to complete a staggering variety of different folding and securing techniques, none as straightforward a process as you might imagine. In fact, many of the formats were personalized and extremely elaborate. As Jana demonstrated with a selection of the Bodleian’s early modern manuscript letters which were displayed (and re-boxed by their curator, Mike Webb, and removed to a sensible distance from the ‘wax table’ when participants queued to have their folded letters sealed) the evidence of this essential practice may still be pieced together from such tell-tale signs as the tears found in the paper, the slits, the holes, and the seals. John Donne devised with his own unique lock that involved a paper hook (yes, said Dan, this turned out to be just like Donne: ‘over the top, witty, and kind of sexy’); and Elizabeth of Bohemia was shown to have tied her letters with exquisite silk thread (just look at this gorgeous replica which was given to me).

We were warned beforehand we would never look at a manuscript letter in the same way again, and the emails of thanks that have flooded in over the ensuing days confirmed this: ‘transfixing’; ‘absolutely bowled over’; ‘I will indeed see them so differently’; and ‘I can’t wait to visit the Reading Room again!’ If you wish to experience a little of letterlocking, it’s well worth setting aside time to watch Jan and Dan’s videos, and to recreate yourself some of these complex and beautiful locking types and their formats. Jana and Dan’s work emerges as a clarion call for letters — so often valued by scholars above all for the information contained in their text — to be considered also as objects.

We were warned beforehand we would never look at a manuscript letter in the same way again, and the emails of thanks that have flooded in over the ensuing days confirmed this: ‘transfixing’; ‘absolutely bowled over’; ‘I will indeed see them so differently’; and ‘I can’t wait to visit the Reading Room again!’ If you wish to experience a little of letterlocking, it’s well worth setting aside time to watch Jan and Dan’s videos, and to recreate yourself some of these complex and beautiful locking types and their formats. Jana and Dan’s work emerges as a clarion call for letters — so often valued by scholars above all for the information contained in their text — to be considered also as objects.

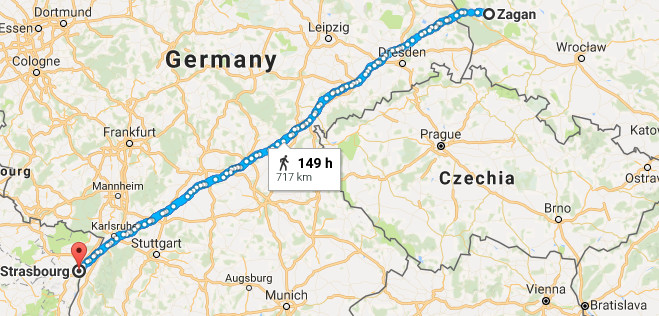

walking pretty much as the crow flies) and his age (he was approaching sixty), and in part because his second wife, Susanna Reuttinger, was heavily pregnant (their youngest child, Anna Maria was born just one month later). Kepler wrote to ask Bernegger, who had helped introduce the couple, to deputize on his behalf, and Bernegger replied with accounts of the wedding. At this point, Kepler had only a few months left to live. Bernegger continued as professor and rector at Strasbourg for the final decade of his life, before dying there on 5 February 1640. Bartsch, the bridegroom at the Strasbourg wedding, edited and published his father-in-law’s Somnium, but is thought only to have lived for a further three years before succumbing to plague.

walking pretty much as the crow flies) and his age (he was approaching sixty), and in part because his second wife, Susanna Reuttinger, was heavily pregnant (their youngest child, Anna Maria was born just one month later). Kepler wrote to ask Bernegger, who had helped introduce the couple, to deputize on his behalf, and Bernegger replied with accounts of the wedding. At this point, Kepler had only a few months left to live. Bernegger continued as professor and rector at Strasbourg for the final decade of his life, before dying there on 5 February 1640. Bartsch, the bridegroom at the Strasbourg wedding, edited and published his father-in-law’s Somnium, but is thought only to have lived for a further three years before succumbing to plague. Of course eagle-eyed users will have spotted already significant new-year additions to existing catalogues in EMLO: as of this week, the calendar of

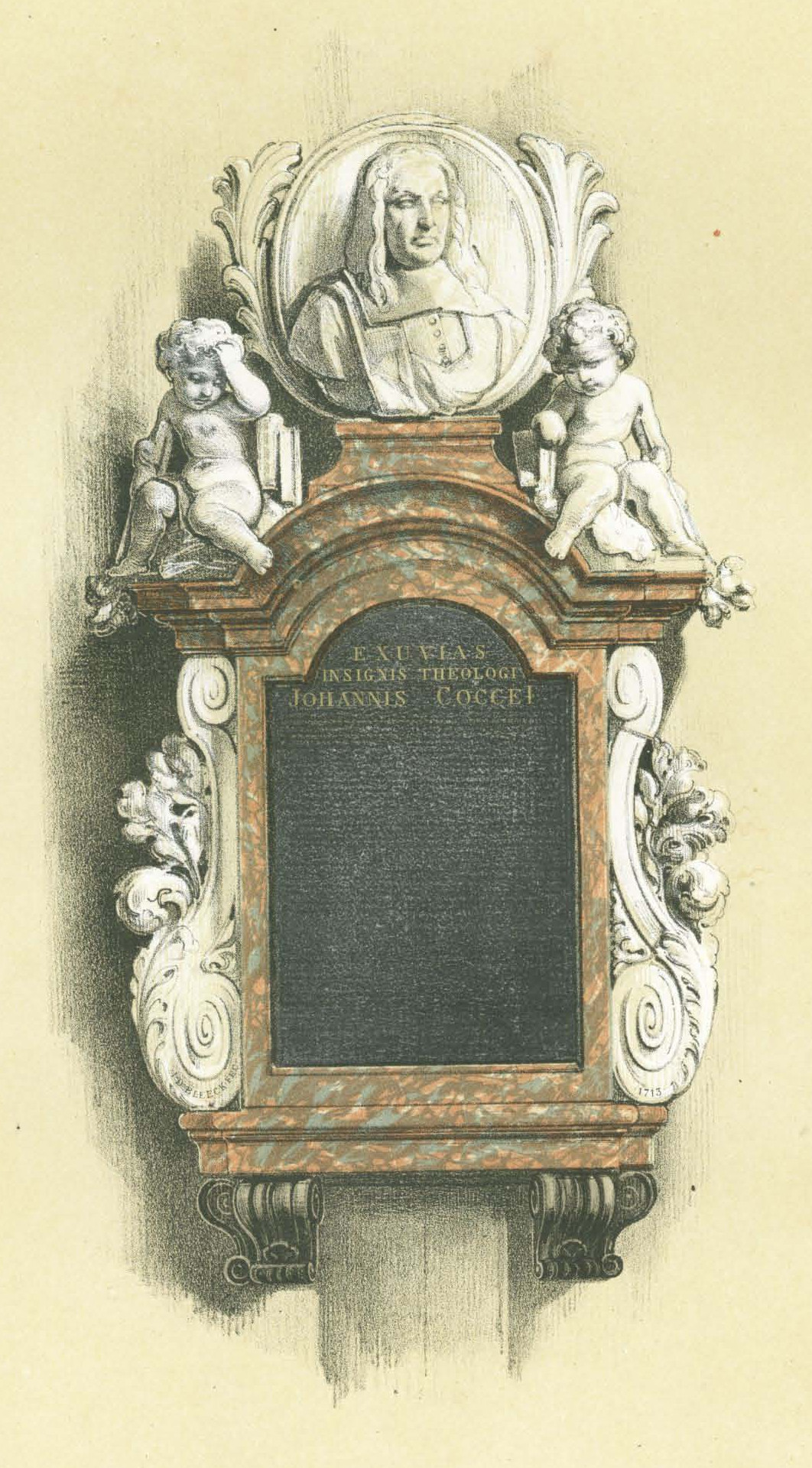

Of course eagle-eyed users will have spotted already significant new-year additions to existing catalogues in EMLO: as of this week, the calendar of

A collaboration between curatorial staff from the

A collaboration between curatorial staff from the